Taking down Damascus in Moscow

By Bilal Y. Saab – There is no question that Washington is suffering from a policy logjam on Syria. The better way to move forward, I say, is by launching high-stakes talks with the Russians. I share the following thoughts on the subject, which appeared in today’s the National Interest.

Other than what it has already tried, there is nothing the United States can do to stop the violence in Syria or make things better for the opposition forces there: this is the conventional wisdom shared by a good number of analysts in Washington and almost ingrained in the minds of U.S. officials working on Syria policy. But there is another strategy worth pursuing with greater urgency: talk tough and bargain with Moscow.

Washington’s policy logjam on Syria is not surprising. There is an acute awareness of the high risks of alternative and perhaps more forceful strategies, be they diplomatic or military. The Obama administration sympathizes with the plight of the Syrian people and is eager to help, but it also does not want to make things worse in that country—and it can’t absorb substantial costs along the way, especially during the fall run-up to the presidential election.

Those who remember the horrors of America’s military intervention in Iraq and the fact that it cost the United States billions of dollars and 4,486 lives so far—not to mention the intangible and indirect costs from the invasion and post-war occupation—may immediately laud the administration for its extra cautious approach toward Syria.

But how much caution is too much? Is Washington being so careful on Syria that it risks undermining U.S. strategic interests in the Middle East?

As things currently stand, the two main U.S. priorities for Syria, containing the civil war and securing the regime’s WMD, are more or less fulfilled. The risk of chemical-weapons loss or usage in Syria is relatively low because Syrian president Bashar al-Assad is not facing a mortal threat—at least not yet. And the sectarian violence inside the country has not furiously spilled over to neighboring countries—again, not yet.

An Agenda for Washington

Does the present calm mean that the United States can afford to watch from afar and do the bare minimum in Syria? Assad may be in good shape now, and the balance of power currently may be tilted in favor of his forces, but several developments could change the dynamics inside Syria in the not so distant future and undermine U.S. priorities there.

Neighboring Turkey is starting to get worried about its own security. The recent firing by Syrian soldiers into a refugee camp inside Turkey (Turkey hosts thousands of Syrian refugees), killing two, has raised the prospects of Turkish military action, with prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan calling for NATO intervention. And it is only a matter of time before Saudi Arabia, Qatar and other neighboring countries actually deliver on their promises to supply the Syrian rebels with substantial amounts of money and modern weaponry. Unsurprisingly, Kofi Annan’s peace plan has failed to stop the violence, thus boosting the chances that military options will be seriously entertained by neighboring countries.

The reality is that a full-blown civil war in Syria is in the works, one that will surely change U.S. priorities in the country. Thus, Washington cannot afford to lead from behind. It is smart to repeat that Syria is not Libya in advancing an argument against military intervention. But it is precisely because Syria is not Libya that Washington cannot merely state its concerns and hope for the best. Unlike in Libya, the stakes in Syria are high, and the United States must take charge, although that does not necessarily mean boots on the ground, another Libya-like aerial campaign or other military options.

Washington’s reactive Syria strategy is at risk of being overrun by events on the ground. A more proactive strategy is desperately needed, one that entails tough bargaining and creative diplomacy with the Russians. The United States needs to know what it would take for Russia to abandon the Syrian regime. If it is continued access to the port of Tartous and business opportunities, as well as healthy trade and strategic relations with the next Syrian government, then so be it. The administration should get it on paper and have the Syrian opposition sign off. There also should be frank discussions about the U.S. policy of NATO expansion.

This high-stakes negotiation with Moscow will obviously not be just about Syria. It will be about the future of the Middle East and U.S. strategic interests—oil, Israel, stability and democracy promotion—in that vital part of the world. Maybe the price of Russian cooperation is higher than this, but it’s high time Washington negotiates with Moscow in a serious fashion.

If Assad loses Moscow as a friend at the UN Security Council, things will get much tougher for him at home. Russia’s change of position could well be the trigger for some real defections in the Syrian government. Yet domestic politics in Washington and Moscow could stand in the way of a more aggressive U.S. diplomatic strategy. Will Barack Obama risk raising the stakes on Syria before November and talk tough with Vladimir Putin? Will Putin play ball at a time when he is trying to reassert himself on the international stage and show domestic opponents that he can defy Washington? It’s possible but not inevitable—and only an offensive diplomatic strategy can keep the possibility open.

Photo: International Herald Tribune.

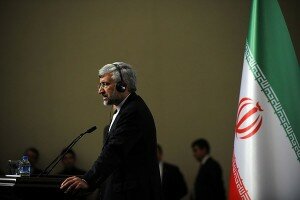

How to assess progress in the Iran nuclear talks

By Chen Kane – I have been thinking lately about ways to assess progress in the nuclear talks with Iran. Yes, handshakes here and there and a “pleasant atmosphere” won’t cut it for me. Here is a very good piece in the New York Times by our colleagues at Carnegie that does the job quite nicely.

Since the negotiations are expected to be long and highly uncertain, Mark Hibbs, Ariel Levite and George Perkovitch provide us with some good benchmarks to measure progress:

Oil prices: The oil market is exceptionally sensitive to the possibility of a military escalation in the Persian gulf; the traders who set prices tend to be sophisticated, with sources of information among policy makers. Global oil prices, which have been above $100 a barrel all this year, are widely believed to reflect a risk premium of $20 to $25. Any significant decline in that premium following the new negotiation round would reflect optimism about the course of diplomacy. It would also further weaken Iran’s economy — putting even more pressure on Iran to negotiate seriously — while helping distressed Western economies and helping President Obama’s chances of re-election.

Access for verifiers: One urgent concession required of Iran is that it grant the International Atomic Energy Agency far greater access to its nuclear plans, facilities, records and personnel. In the absence of this, most other steps would ring hollow, making it unlikely that sanctions on Iran would be phased out — a goal high on Iran’s list of demands. Since time would be needed to test Iran’s sincerity about disclosures, and its cooperation with the atomic energy agency after years of delay and deceit, Iran’s willingness to under take such steps early on would both be a prerequisite for, and a signal of, progress on the negotiations.

The bargaining issues: If the focus of talks remains stuck on an attempt to resurrect an earlier deal to trade a foreign supply of nuclear fuel for Iran’s agreement to ship its existing stockpile of enriched uranium out of the country, the diplomatic process will be headed in the wrong direction. Such a deal would fall short of what Iran and its counterparts across the table need in order to end the crisis. Anything less than early Iranian gestures on suspending higher levels of enrichment and conducting enrichment outside its commercial facility at Natanz would most likely doom the negotiations to failure. So would a refusal by the other side to suspend the implementation of new sanctions if Iran extended such gestures.

U.S.-Iran dialogue: In earlier rounds, Iran usually resisted conducting parallel direct discussions with the United States on the margins of the six-party talks. Yet such one-on-one dialogue is essential for success. Iranian willingness to relax its position, and American willingness to sustain bilateral dialogue in an election year, could indicate a prospect of resolving the nuclear crisis.

Frequency and duration of meetings: Previous unproductive negotiating rounds have been truncated and followed by long pauses. Such pacing would be inconsistent with the urgency of this round. Anything but frequent and prolonged negotiating rounds (though some might be unpublicized or employ back channels) would indicate that the negotiations were headed for failure.

A summer deadline: Sorting out all the issues associated with Iran’s nuclear program, let alone other issues that include Afghanistan, Iraq, support for terrorism and human rights, would take a long time. But in the absence of visible progress by the end of June, new sanctions will go into effect, making it even more painful for Iran to negotiate under pressure. Israel would be likely to conclude, in such a case, that the only option left was military. Diplomacy, in other words, has 11 weeks to yield results. Still, it is not unrealistic to think that most of the criteria described here could be met in the first round of renewed diplomacy — if Iran and its counterparts are determined to move from crisis to problem-solving.

Personally, I found the last point made to be the most interesting – – – the three argue that diplomacy has 11-weeks to yield a favorable result. If these negotiations fail, Israel, according to the authors, may be left with the military option. That’s an interesting observation from an Israeli ex-official (full disclosure, Eli was my boss). I, however, disagree. I would give negotiations more time to achieve their full potential, though how much more I am not so sure.

If negotiations then fail, my guess is Israel will act militarily in December 2012. It would happen after the November 2012 General Election in the United States and before the Presidential Inauguration in January 2013. You may recall that the 2012 WMDFZ conference is planned for December later this year. Aside from the text of the Action Plan requesting the conference to take place in 2012, the conference date was chosen for precisely the same reasons – – it is after the U.S. elections and before the inauguration. So, December 2012 is shaping-up to potentially be a very busy month in the Middle East…

Photo: Ma Yan / XINHUA / LANDOV

These are all weaknesses in th

Richard! Does Aussie Dave know

Postol's latest publication ab

Mr. Rubin, I am curious if you

Thank you Uzi. You have obviou

Bruce came back to CSTPV's 20t

Bruce came back to CSTPV's 20t

Thanks for publishing in detai

The 'deal' also leaves Israel

I think that Geneva Talks pose