Special roundtable: 2012 MEWMDFZ conference

By Bilal Y. Saab – This took longer than I expected, but it is finally out. For expert commentary on the 2012 conference on a WMD-free zone in the Middle East, I urge you to take a look at this CNS special roundtable report. It includes contributions from 12 specialists in the field of arms control in the Middle East. My essay (I am lead editor of the report) takes a long-term view at the future of arms control in the Middle East in light of the Arab uprisings. Here it is again, along with that of Chen Kane, my partner in crime, but I really recommend you read the other pieces as well.

The Road Ahead

Bilal Y. Saab

If a conference on “A Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction Free Zone in the Middle East” does take place in December 2012 in Helsinki, it would not be the first time Middle Eastern nations meet in the Finnish capital to address underlying sources of regional insecurity and instability.

Indeed, more than seventeen years ago, delegates from all regional participants in the ACRS talks, along with the gavel-holders (the United States and Russia), the host country (Finland), and experts from Australia, India, France, and the United Nations, met to discuss all things arms control and regional security. While modest progress was achieved on some of the conceptual and operational items in ACRS, the talks ultimately collapsed in 1995, primarily because Egypt and Israel disagreed over a disarmament strategy and timeline (Israel is the region’s only nuclear weapon state). Assuming it happens later this year, will the 2012 conference produce more positive results? Most analysts, including participants in this roundtable, are skeptical, and perhaps rightly so.

Nobody doubts that it will take years, if not generations, for arms control to take root in the Middle East. With no end in sight to the Arab-Israeli conflict, with increasing regional uncertainties caused by the Arab uprisings, and with talk of possible military action by Israel and/or the United States against Iran to halt or destroy its nuclear program, the prospect of states in that part of the world cooperating with each other like they have never done before and placing real, verifiable, and mutual limitations on their state sovereignty, national secrets, and defense armaments for the collective goal of reducing regional insecurity indeed seems unthinkable at present.

The Middle East will experience growing pains should regional states decide to resume the long interrupted arms control process and participate in the 2012 conference. Any casual reading of the arms control experience between the Soviet Union (later Russia) and the United States and among European states after the end of the Cold War will clearly show that arms control—already a counterintuitive concept and exercise even to the most liberal and open-minded—is tough and complex business.

Much has changed in the Middle East since the ACRS period of the 1990s. Iran is much closer today to achieving a nuclear weapons capability (if it so chooses) than it was years ago. With Saddam Hussein out of power since 2003, Iraq is no longer a confrontationist state in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Iraq’s recent radical shift in politics has resulted in a Shi’ite-majority government that is increasingly under the influence of Iran, though the situation in Baghdad remains unstable. Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Turkey have increased their regional power and influence at the expense of Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya are transitioning from authoritarianism to representative government following their popular uprisings. Finally, Syria is in a state of civil war that could engulf several states in the region. If Damascus falls and a new anti-Iranian leadership comes to power in Syria, Tehran will lose its only real ally in the Middle East and its most important access to the Arab world. These changes (actual and potential) notwithstanding, many of the old problems plaguing the Middle East—territorial disputes, arms races, security dilemmas, historical rivalries, and religious, sectarian, and ethnic animosities—persist.

All of these fluid security and political dynamics present a wide array of challenges to the 2012 conference in particular and to the future of arms control in the Middle East in general. But they also present potential opportunities, depending on how the political transitions in the region unfold. The biggest long-term opportunity I see is the gradual change in the overall political landscape of the Arab world and in the domestic context of Arab foreign and defense policy.

Current and emerging leaders could be more receptive to new thinking and practices in foreign and defense policy. Even if they prove to be worse than their predecessors, they will still operate under vastly different political circumstances, i.e., facing greater societal demands and political pressures that could positively impact foreign policy decision-making. For example, if Arab publics call for regional cooperation on security and nonproliferation, their national governments-Islamist and secular-will have to comply with their wishes. Otherwise, they will face political costs.

In addition to new leadership, the political transitions in the Arab world are likely to empower parliaments and free judiciaries from the grip of all too powerful executives. Indeed, Arab parliaments and judiciaries no longer have to be symbolic, powerless, and rubber-stamped institutions, and can play a more effective role in foreign affairs. Arab parliaments should be empowered to fulfill the goals of legislation, oversight, accountability, regulation, and constant renewal of political life. But they can also play an extremely constructive role in arms control by ratifying treaties, financing foreign policy proposals, approving defense budgets, and overseeing weapons systems to the best they can.

In a similar vein, Arab bureaucracies no longer have to be used by dictators to sustain their patronage policies. Instead, today there is an opportunity to stop the trend of staffing the bureaucracies and intelligence services with regime loyalists who are instructed to suppress and spy on society. If properly handled by the new leaders, intelligence services can be used to perform necessary national tasks, including defending the homeland and assisting with arms control-related verification mechanisms, if the opportunity presents itself. Absent real intelligence reform in the Arab world and no less than a revolution in these services’ mission and standard operating procedures, regional arms control is likely to face some serious technical problems.

As far as civil society is concerned, its recent resurgence and the empowerment of the public in the Arab world are positive developments that will help ease and speed up the transition to democracy. Open societies tend to form governments that are more competent and better at integrating and incorporating the input of as many skilled and specialized voices from outside the government as possible. Closed societies, on the other hand, tend to form less than effective governments because they have a much smaller pool to choose from, often paying more attention to factors like loyalty and ideology at the expense of skill and capability.

The importance of the involvement of civil society in the arms control process cannot be overstated. The instrumental role that American civil society and industry has played in supplying the United States government with knowledge about and technical resources for arms control—including nuclear power, chemistry and biology, weapons systems, radars, sensors and overhead reconnaissance satellites—has helped the United States successfully negotiate and sign a number of arms control treaties including the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty and the Chemical Weapons Convention. Even the most competent governments need the expertise and specialized skills of practitioners, scientists, and companies from the private and nonprofit sectors. In arms control, public-private collaborations and partnerships are a must given the field’s complexity and multi-disciplinary nature.

The Arab world’s governments do not have a stellar record of engaging their civil societies and seeking from them the necessary knowledge and skill-sets to better perform at public policy and foreign affairs. Of course, some governments are better than others. Obviously, the more open the political system is, the more opportunities and avenues civil society will have. Unsurprisingly, the idea of empowering civil society or including it in governmental decision-making has been anathema to Arab autocrats who viewed it as a political threat. With new political opportunities now forming in the Arab world and civil society being allowed to operate with more freedom after all these years of suppression, real investments in education and science and technology—necessary for creating and nurturing an arms control culture—are now possible.

While one could argue that public opinion in the Arab world did not generate significant political costs to old autocrats as they engaged in foreign policy (one notable exception, however, is the assassination of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat for his unpopular peace treaty with Israel), this is more likely to change. Through popular will and mandate, Islamists and liberals (in fewer numbers of course) are coming to power in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and possibly elsewhere, and should these new rulers fail to deliver and fulfill their promises, public opinion will not be kind to them and may force political adjustments or resignations.

Of course, the pace and scope of widespread change in the Arab world is largely dependent on the changing role of the militaries and law enforcement agencies, i.e., the remnants of the ancien régime. One cannot speak of a new social contract in the Arab world if the militaries retain their supraconstitutional powers and firm hold on national politics. Take Egypt, for example, where the fight between the Islamists and the liberals on the one hand (i.e., those who led the popular uprising), and the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (the ruling military council) on the other will determine the future of the country. We can expect similar political battles and rocky transitional scenarios to take place in Syria should the regime of President Bashar al-Assad collapse and the armed rebels take over until a new government is formed.

In sum, for arms control in the Arab world to have a better chance to succeed, civil-military relations should be relatively sound and the role of the military in society should be properly defined; the military services should not obstruct the natural flow of politics and instead answer to the civilian authority whose agents are solely responsible for making and conducting foreign and security policies, and not the other way around.

We have no choice but to wait and see how the new leaders of the region will approach issues and how amenable they will be to new and more cooperative approaches in foreign affairs, including arms control. Should the transition succeed and real, drastic reforms in political and economic affairs take place, the next big test for Arab societies will be to start building durable and effective governmental, institutional, administrative, and technical capacity in order to deal with a host of domestic and foreign policy challenges. That in itself is a process that is likely to take an even longer time.

It is one thing for nations to be free, but quite another to be prosperous and competent at home and in their dealings with the outside world. The Middle East could open up politically but remain mired in bureaucratic under-development and economic slump. Smart national leadership can prevent that from happening.

Bad Timing But Still Some Hope

Chen Kane

The decision of the 2010 NPT Review Conference to hold a conference on “A Nuclear-Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction-Free Zone in the Middle East” was part of a compromise between the United States and Egypt (the latter as Chair of the Non-Aligned Movement, the New Agenda Coalition and a leading country in the League of Arab States). This US-Egyptian agreement was intended to facilitate a consensus text for the 2010 NPT Review Conference. Specifically, Egypt got Iran to agree on the consensus document in exchange for the United States promising to launch the 2012 conference.

It is important to mention the background story behind the 2012 conference because both Egypt and the United States are currently unwilling to hold or incapable of holding (or both) the conference in late 2012, but both also do not want to openly admit it. Current Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi has been in power for a month, and his ruling party has no experience in government or in pulling the levers of power. Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood have yet to start articulating Egypt’s domestic, security, and foreign policies, and it is unclear who will actually decide on international affairs for the country; will it be the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces or the president?

The power struggle between those two blocs has just started and will take a while to resolve. The Egyptian Foreign Ministry has made it clear that the current situation in the region should not be used as an excuse for postponing the conference, but the ministry also lacks strategic instructions or a coherent planning mechanism for what they want to achieve in such a high-level forum. Should the conference be used as a venue to further isolate Israel or to start a constructive regional security dialogue?

The United States is not in a better position, either. It is presidential election season in Washington, DC. One only has to hear US officials commenting on the conference to conclude that the United States is unable to invest any political power to make it happen (perhaps after the November election, but not before the scheduled month of the conference in December). Conference facilitator Jaakko Laajava and his team have been working extremely hard to reach an agreement on some terms of reference, an agenda, and follow-through for the conference, but they lack the influence and authority to make things happen, assets that only the United States possesses in its relations with many Middle East nations, most importantly with Israel. With such a demonstrable lack of US interest, it is extremely unlikely that Israel will prepare any constructive ideas to kick-start the conference, especially since it opposed the conference in the first place.

With this background in mind, I believe that the agreement to hold the conference has been reached for the wrong reasons and its timing could not be worse. That said, I do not think that holding a conference is a bad idea. I do believe that it is in the best interest of all countries in the Middle East to convene and openly discuss all the security issues facing the region. But here is the main question: are countries in the region ready and do they have the proper incentives to come to the negotiating table and talk directly to each other? No matter how significant the threat of failing to reach consensus in the 2015 NPT Review Conference is, if the states in the region are not ready to engage in a constructive dialogue, the process will simply not start.

Should they prove their readiness to talk, here are some useful ideas regarding both process and substance that can be agreed upon for the conference:

• States in the region have not met for more than seventeen years since the collapse of the ACRS talks, and some of them did not participate in (Syria and Lebanon) or were not invited to (Iran, Libya, and Iraq) the ACRS talks. There is a great deal of bad history in the region and tensions must be relaxed. States will need time to deliver “national statements,” and speak about their concerns and threat perceptions. This is crucial because if states are not given the proper amount of time to do this healthy venting exercise on the first day of the conference, they might do it throughout the meetings, rather than engage in a constructive dialogue and achieve tangible results.

• While countries in the region may not be willing to work together right now, they may be willing to take unilateral steps to enhance regional security. The model of the Nuclear Security Summit where every country brings a “house gift,” a measure it is committed to implement unilaterally or as a sub-group by 2015, can be adopted. Starting with unilateral steps is likely to create a momentum for working toward a common goal, even if these commitments are not taken in unison.

• If a follow-up meeting or process is agreed upon, it would be best to start with the technical issues. While the region may not be ready to solve the political-strategic issues yet, especially while the governments of the major regional players are consolidating power, there are technical issues that can be discussed. One example would be a discussion on how to create a verifiable zone free of chemical and biological weapons and their delivery systems, including missiles.

• Regional civil society, and especially the youth, should have a say and a role to play in the prospective zone. A Finnish NGO should host a meeting in parallel with the conference (similar to the NGO meeting held in parallel with the Nuclear Security Summit) for international NGOs and next generation practitioners from the region to come together outside the bounds of official government talks. Such a parallel conference may create even more important opportunities to promote dialogue and support fresh ideas in conjunction with the official talks.

Egypt’s nuclear politics

By Egle Murauskaite – Before the second round of Egypt’s presidential election was held, a curious Egyptian announcement stated that the country’s plans to construct a 1,000MW nuclear power plant – frozen following the revolutionary events of 2011 – have been revived. While Egypt has the right to a full nuclear cycle under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) it has consistently promoted regional nuclear disarmament for over thirty years. With the international community gradually coming to terms with nuclear (though not nuclear-armed) Iran, Egypt could be looking to increase the stakes in the upcoming 2012 Conference on a Middle East Weapons of Mass Destruction-Free Zone, potentially pursuing a policy of nuclear ambiguity.

In fact, such nuclear ambiguity is nothing new in Egyptian nuclear diplomacy. Up until the Six Day War in 1967, Egypt was aggressively advancing its nuclear infrastructure and harbouring nuclear weapons ambitions – the investments have subsequently stopped and the weapons program was abandoned. In 1968, Egypt signed the NPT, but delayed ratification until 1981 (as a bargaining tactic to induce Israeli cooperation on nuclear disarmament which failed), and in 1974 Egypt and Iran submitted a resolution to the UN General Assembly, calling for a nuclear weapons free zone (NWFZ) in the Middle East. Over the years a number of Egyptian officials and clerics have made statements regarding the country’s nuclear aspirations. Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak famously said that “if the time comes when we need nuclear weapons, we will not hesitate.”

Egypt’s traditional rhetoric of nuclear ambiguity has been less than credible. Historically, strong relations with the United States, as well as highly demanding financial and technological aspects of a weapons program, have constrained Egypt. Already in 1995, its threats not to sign the indefinite extension of the NPT were taken with a high degree of skepticism, not to mention Egypt’s recent threats to withdraw from the treaty if the 2012 Conference fails. Egypt’s decision to expand its nuclear energy program could certainly be one way to add teeth to its nuclear ambiguity claim. Such a move would also serve as a not-so-friendly reminder of the urgency of the WMD-free zone.

Naturally, there is always an argument to be made about the country’s growing energy needs. However, given the tense atmosphere surrounding the nuclear issue, Cairo is very well aware of the political ripple effects that would most likely ensue should there be any departures from the status quo. The drama surrounding the Iranian nuclear standoff has sensitized the international audience to such an extent that the slightest hint of posturing by any regional state is likely to cause alarm.

Like many other countries in the region, Egypt started its nuclear energy program under Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace initiative, with the first 2MW research reactor constructed by the Soviet Union over 1954-1961 in Inshas. Its second (22.5MW open pool) research reactor was built in 1992-1998 under a contract with Argentina. The research reactor while producing only small amount of plutonium, with the hot cells, could have provided Egypt with the initial basis for a nuclear weapons program. Egypt certainly possesses substantial expertise to advance a nuclear program, with over 1,400 trained scientists, 2,300 technical staff, and a support staff of around 1,300.

Egypt’s nuclear program has already come under IAEA scrutiny over compliance issues. In 2005, the Agency found that Egypt failed to report its uranium irradiation experiments conducted over 1990-2003, and to include imports of uranium material in its initial inventory. While the Director General’s report concluded that there was no explicit policy of concealment, the Agency’s lenient approach in face of these violations raised concerns internationally. Moreover, while the investigation established a benchmark, making similar future activities highly visible, Egypt continued on this pattern: traces of highly enriched uranium were detected at Inshas in 2007 and 2008, necessitating repeated IAEA probes.

On July 9, 2012, the Ministry of Electricity and Energy presented the feasibility study on the construction of a nuclear power plant in al-Dabaa for new Egyptian President Muhammad Morsi to review. Pressure on the new government to assign the limited economic resources to priority areas will likely be a major determinant of the project’s pace. Below are some thoughts on the program’s direction.

One, a decision will have to be made whether or not Egypt will seek to master the full nuclear cycle. The hot cells at the Inshas site already provide some reprocessing capacity, and having learned the process in principle, scaling up would not be difficult. Such a development, or pursuit of enrichment technology (less likely), would send a strong signal about the country’s willingness to ‘keep its options open’.

Two, Iranian-Egyptian rapprochement would be a way to raise concerns on the proliferation front, even if it is confined to rhetoric. Said Jalili of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council has already suggested that Iran would be willing to extend cooperation on “peaceful nuclear energy.” While Egypt is not likely to depend on Iran for its nuclear program, closer relations between Iran and Egypt, in the face of international efforts to isolate Iran, do not bode well.

Three, Egypt’s decision regarding the ratification of the Addition Protocol may ultimately determine if it can actually purchase nuclear reactors for the power plant at the end of the bidding process. Before the project was frozen in 2011, a number of international companies had expressed interest, including Rosatom (Russian), KEPCO (South Korean), Areva (French), Siemens (German), Hitachi (Japanese) and Westinghouse (American). Adherence to the Additional Protocol is required by vendors – explicitly by Japan, or implicitly by others using technology that originated from the U.S. – and presently, even Russia seems unlikely to try and bend these regulations. On the other hand, Egypt’s accession to the Protocol would diminish the ambiguity of its nuclear stance even further.

Four, Egypt’s potential effort to reach out to the Gulf States for investments in the project would be the surest way not only to secure funding but also to give these countries a sense of practical involvement. That Morsi chose Saudi Arabia for his first official visit may point in this direction.

Maintaining a credible stance of nuclear ambiguity will require Egypt to engage in a delicate balancing act: rocking the boat just enough to remind Israel that it is not off the hook regarding nuclear disarmament, but at the same time placating the Gulf states (and the U.S.) that fear a nuclear arms race in the region. However, as the momentum for the WMDFZ Conference seems to be petering out, with the Iranian nuclear program under increasing international scrutiny, Egypt may feel it is worth raising the stakes.

Egle Murauskaite is a research assistant at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies.

Interview with Sitki Egeli on Syrian-Turkish incident

By Bilal Y. Saab – The incident of the downed Turkish jet by Syria’s military a couple of weeks ago continues to raise important questions. I think we have yet to fully uncover the real security and political implications of that event. Furthermore, despite increasing news reports and (perhaps because of) official statements by Damascus and Ankara, we are still not 100% sure what really happened, given the almost opposite narratives by the Syrian and Turkish authorities. My suspicion has always been that the mission of that Turkish jet, regardless how long it was flying in Syrian airspace, was twofold: take as many photos of Syrian military infrastructure as possible and perhaps more importantly test command and control of Syria’s armed forces (in addition to testing the nature of its air defenses’ responses and the coverage of its radars).

Sitki Egeli, one of Turkey’s sharpest defense analysts, writes independently on various security and military topics, including air power, weapons of mass destruction, nonproliferation, and missile defense. Dr. Egeli holds a Ph.D. in International Relations from Bilkent University and he is the former Director for International Affairs of Turkey’s Defense Industry and Procurement Agency. He currently works at an international defense consulting firm in Ankara, Turkey. I first met Sitki earlier this year in Lake Como, Italy during a workshop sponsored by the Italian Foreign Ministry on the technical details of a WMD-free zone in the Middle East. We hit it off right from the start. His comments during the discussions were spot on and his extensive knowledge of military affairs is quite impressive. The following interview I did with Sitki is intended to shed more light on the puzzle of the Syrian-Turkish military encounter; hopefully it clarifies some important, unresolved issues in the story.

1- What kind of Turkish jet was downed by the Syrian military? It seems like there are conflicting reports out there on this issue.

Indeed, some inaccurate and misleading accounts on the type and capabilities of the jet have surfaced. For example, some claimed that it was a variant of F-4 fighter used to suppress enemy air defenses, implying an offensive or provocative mission. This is simply wrong. Some perhaps confused RF-4 with F-4G variant, which has never entered Turkish service and was used exclusively by USAF.

Now, to set the record straight, the Turkish aircraft that was shot down was a US-built RF-4E, which happens to be photographic reconnaissance variant of the venerable, Vietnam-era Phantom jets. It joined the Turkish Air Force in 1980 and was one of the 18 surviving examples still flying after 3 decades in service. More recently, Turkish RF-4Es including this one had gone through a limited upgrade to keep them flying for another decade. This saw relatively modern navigation, communication and electronic self-protection systems added to the aircraft.

2- Please explain to us its capabilities. What is the typical mission of those kinds of jets?

At least in theory, RF-4E retains a lot of the capabilities present in F-4 fighter-bombers. But this is deceiving. The machine gun to be found in regular F-4s is replaced with a camera bay, and RF-4’s modified radar does not allow firing of the more advanced, longer- range missiles. Therefore, unless there is an emergency, RF-4s do not carry weapons and do not perform armed missions. Their mission payload is confined to an array of day and night cameras used to take snapshots of points of interest. Remember the famous photos of Soviet ballistic missiles to have triggered the Cuban missile crisis some 50 years ago? Those are exactly the type of photos captured and this is typically the sort of mission flown by RF-4E. In other words, very high-speed runs over or near the area of interest, typically at very low altitude to avoid detection by radars and SAM batteries.

But, I am puzzled with one aspect here. Turkish RF-4E can also carry under wing pods housing cameras with much longer-ranges, hence no need to get dangerously close to Syrian territory. Same mission could have been performed by staying well beyond Syrian territorial waters. So, perhaps the Turkish account is accurate and the aircraft was not on a reconnaissance mission, but was testing the coverage of Turkish air surveillance radar to the north. Or perhaps by flying very close to the Syrian coastline, RF-4 was trying to incite Syrian air defense radars and systems in order to reveal their order of battle and to identify their electronic signatures. Or perhaps another as yet unknown mission. This aspect is up to speculation and would probably not be known for a long time to come, if ever.

Now, one more note on the capabilities of RF-4E in question. Besides cameras, the aircraft was fitted with radar warning receivers (RWR). What the latter does is to warn the pilots when their aircraft is “illuminated” by “hostile” radar. The device gives further warning if tracking radar found on surface-to-air missile (SAM) batteries locks on the aircraft, implying that launching of a surface-to-air missile is imminent or has already taken place. The pilots would then change course and altitude, initiate evasive maneuvers, or they can deploy passive defensive aids such as chaff to fool radars. This is a basic electronic self-protection device to be found on most if not all fighter aircraft since Vietnam War years.

3- What do we know about enemy fire? Was it a Surface to Air Missile (SAM) or Anti-Aircraft Artillery?

Whether it was a SAM or anti-aircraft artillery to have shot down the RF-4E is hotly contested between Turkish and Syrian authorities. The Syrian side claims the aircraft was brought down using anti-aircraft artillery, implying it was flying very close to the shore, because effective range of such barreled weapons is hardly more than 2 NM (nautical miles) – well below Syria’s 12 NM territorial waters.

Conversely, Turkish military contends that RF-4E was hit on the edge of Syrian territorial waters. It then went out of control and crashed some 8,5 NM off the coast. Therefore, a SAM offering longer ranges must have been used. Yet, Turkish authorities also admit that no electromagnetic emission coming from SAM batteries was detected during the incident; thence, they claimed, a laser or infrared guided SAM must have been used. What was the basis of this claim? Remember this radar warning receiver installed on the aircraft? Given the existence of such device, if the aircraft was targeted and shot down by a radar guided missile, then its crew would knew that a missile was approaching and would have 30 seconds or more to inform their superiors that they came under attack. This did not happen. So, either a missile using another means of guidance (laser, infrared, CLOS etc) was used and pilots had no warning, or RF-4 was much closer to the shore and fell prey to anti-aircraft artillery.

Yet, claims based on a Sam using laser or infrared guidance hit another stumbling block: there are no known SAMs of such guidance mode in Syrian inventory to achieve a kill at such range (+12 NM). The closest candidate, SA-22 of Russian-supplied Pantsir air defense system (picture above), could have reached 10 NM at most, and some sort of radar cueing still being necessary to initiate the engagement sequence.

Please be warned that a lot of details are still sketchy, thus highly speculative. All those conclusions and judgments may have to be revised as the details continue to surface. Accounts of other parties, such the images that must have been obtained by the powerful British radars in Cyprus, may shed further light on what actually happened.

4- Is Syrian president Bashar Assad telling the truth when he says that he wished his military had not fired on the jet and that they did not know it was Turkish? What does that say about Syrian command and control?

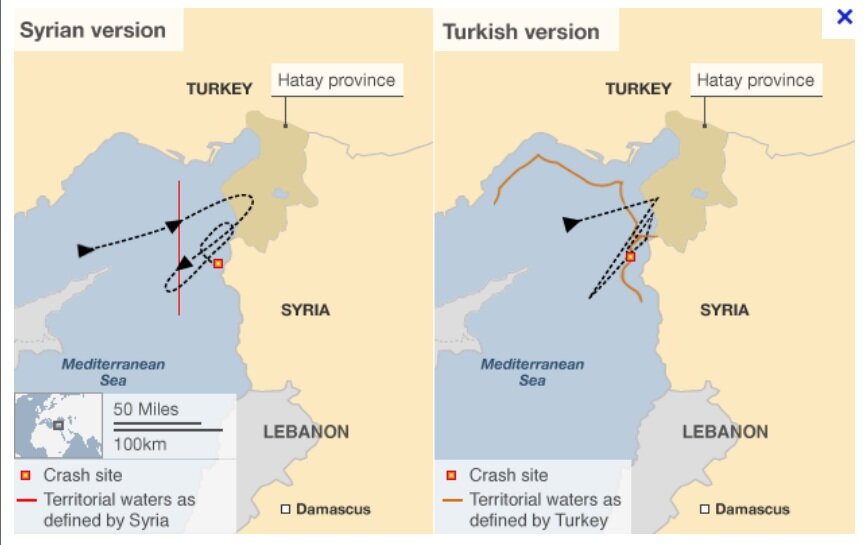

Aircraft’s track information captured by Turkish radars (identical to Syrian version till the last 60 seconds) and publicized by Turkish authorities (see map) holds a number of interesting clues.

First of all, RF-4E was flying in the immediate vicinity of Syria for at least 40 minutes prior to meeting its fate. Thus, it is hard to believe Bashar Assad’s statement that the Syrians did not know this was a Turkish plane. Unless of course, Syria’s air defense command chain is truly dysfunctional or severely stricken, which I don’t find very plausible. Besides, the Turkish transport plane that reached the area shortly afterwards to search for the wreckage was also fired at, which further weakens Syrian claims that they could not identify those aircraft.

Second, 15 minutes before being shot at, RF-4E had violated Syrian air space for roughly 5 minutes and flew a south to north course parallel to Syrian coastline and at very low altitude (100 ft!). When it reached the Turkish coast, it turned around and began flying north-south in a course parallel to the previous run, but this time at a higher altitude and on the edge of Syrian territorial waters. When it reached the point where it had begun its previous violation, either it was shot down and drifted towards the coast before plunging into the sea, or it turned towards Syrian shores to repeat its previous run, but entered within effective range of Syrian anti-aircraft guns already alarmed to the presence of a low-flying aircraft and waiting with fingers on trigger.

I would presume that during the first violation, Syrian air defense crews closest to RF-4E must have contacted their superiors one level up (command center at Homs, Turkish authorities suggested), and asked for instructions. Probably, they have been told to shoot if the aircraft came back and entered within their range. And they simply followed their instructions!

5- How do you assess the performance of Syria’s air defense network? Is it as potent as many think it is? Can’t the U.S. Air Force and NATO jets fly over Syrian airspace, destroy the key nodes, and try not to get hit?

For sure, they managed to bring down a high-speed, low-flying western plane belonging to a well-trained NATO air force. Whether this was a centrally controlled act following clear instructions from the top is difficult to judge. Such airspace incursions take place on a routine basis in the region, over the skies of Cyprus, Aegean littoral or even Syrian-Turkish border. But, no one had resorted to such an extreme reaction of pulling the trigger and shooting down without any warning. Except, of course, back in the 1990s when Syria again shot down a Turkish civilian mapping aircraft inside Turkish air space! That one had turned out to be a case of miscommunication between Syrian pilot and his ground controller.

In case of the more recent incident, the normal procedure would have been for Damascus to issue a diplomatic note of protest and warning (e.g., don’t continue with such incursions, or I will take necessary action). Or perhaps, the Syrian air force could have scrambled a few fighters to force the intruder out. Or under worst circumstances, perhaps few warning shots with tracers by the nearest coastal battery. But, definitely not a shoot-to-kill engagement without warning! Perhaps the instructions were given to Syrian air defense elements to fire at any western aircraft that came close to Syrian airspace – to signal the regime’s determination to resist any foreign intervention or creation of a buffer zone etc. Conversely, if there were no such orders, then this incidence may as well imply poor training, low degree of professionalism or perhaps over-the-edge psychology of Syrian air defense forces.

For one thing, by virtue of Soviet/Russian-supplied and upgraded air defense weaponry in Syria’s disposal, as well as the more organized and robust nature of Syrian military, no one should expect something similar to the catastrophic failure of Libyan air defenses. On the other hand, it would be very naive to expect that in the event of a major conflict or intervention, US and NATO fighters would be flying into Syrian air space before Syrian air defenses are effectively neutralized by information and electronic warfare techniques, cruise missile and stealth aircraft strikes, against which Syria’s old-fashioned and rapidly aging air defense network would simply become irrelevant.

These maps are provided by Dr. Egeli. They show the Syrian and Turkish versions of the incident as well as the jet’s mission profile, as explained by Turkey (the blue map).

Interview with Kenneth M. Pollack on Persian Gulf security

By Bilal Y. Saab – Ken Pollack needs no introduction. One of my favorite analysts of the Middle East, a good friend, and a former colleague, Ken is a Senior Fellow at the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings (formerly the Center’s Director). Ken’s government experience includes stints at the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Council, focusing on the Persian Gulf. I sat down with Ken last week to discuss security affairs in the Middle East and specifically, his new paper for the Saban Center called Security in the Persian Gulf: New Frameworks for the Twenty-First Century. Needless to say, I strongly recommend your read the paper, and if time is short, you can always take a look at the executive summary.

1- US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton recently proposed improved collaboration with GCC states on maritime security and missile defense to counter potential threats from Iran. One of the fruits that could come out of enhanced US-GCC relations is a regional missile defense system for the Arab Gulf. How realistic is such a system knowing the classic challenges and limitations of missile defenses?

As you point out, we should not expect a whole lot in tangible terms from a regional missile defense system for the Gulf. Even with advances in recent years, such a system is likely to miss more than it hits. It might also be extremely expensive—and might not be the best use of such funds for countries (including the United States and Saudi Arabia) that probably would be better off using that money to address deep structural problems in their economies and societies. That said, if the costs are bearable, there are definitely some important plusses to going ahead with such a program. First, it provides another tangible sign that the GCC has no intention to bow down before a nuclear-armed Iran, but will instead balance against Tehran however they can. Second, it is another symbol of American commitment to the defense of the Gulf—something that many people worry about if Iran acquires a nuclear capability. Third, it would help further integrate the defense and security strategies of the Gulf Arab states and the United States in the Gulf. It would further smooth cooperation and be one more physical incentive for all of the states of the region to work and act in unison, and in lock-step with the United States, all of which would be helpful in deterring Iranian aggression, reassuring the Gulf Arabs, and ensuring cooperative moves both among the GCC states and between the GCC and US.

2- Calls for and discussions about a new regional security architecture are old. From the 1991 Gulf War to the Arab Spring, has anything changed in the Middle East to make that vision possible and what role should the United States play to make it happen?

You are right that these ideas date back twenty years, and the original rationale for them remains germane: the GCC architecture is helpful, but it only takes you so far. In particularly, it isn’t of much help if your goal is to create a framework for arms control in the region and/or developing a more cooperative approach to security problems with Iran and Iraq. However, there are three things that have changed since the Persian Gulf War. First, Iran has made much greater progress toward acquiring a nuclear capability of some kind, and that is an important new threat that all of the Gulf States and the U.S. now must confront. Second, Saddam Husayn is gone, and Iraq is in the hands of a new leadership that everyone hopes will be more peaceful than he was. While the jury is still out on Iraqi stability, let alone aggressiveness, the nature of that threat has changed considerably and if Iraq somehow manages to stumble toward stability, it would be helpful for Iraqis, Gulf Arabs and Americans to find a way to deal with its security needs in a collaborative framework. Finally, the GCC states and the United States have made considerable progress in knitting together their communications, intelligence, air defense, and naval networks, which provides a strong foundation for further cooperation. So there is both a greater need and a greater potential for an expanded and transformed security architecture.

3- In what ways has the Arab Spring changed traditional security dynamics in the Middle East? Specifically, should Damascus fall, are we truly about to witness a radical shift in the regional balance of power?

This is a big topic and for a fuller treatment, I would refer you to the essays that I wrote in the collaborative volume The Arab Awakening: America and the Transformation of the Middle East (Brookings, 2011). The thumbnail sketch is that the Arab Spring is likely to have a profound impact on the security dynamics of the region. Even more than the Iraqi civil war, it has created the threat of a Sunni-Shi’a conflict in the region—something that the civil war in Syria is really helping to generate. It has created the prospect for further realignments in the region: democracies vs. autocracies, haves vs. have-nots, Islamists vs. secularists. I am not saying for certain that any of this will happen, only that the events of 2011 and 2012 have completely reshuffled the Middle Eastern deck and we cannot be certain how the states of the region will align themselves when the next hand is dealt. It might very well be completely different from our traditional prisms for viewing security dynamics in the region like pro-American vs. pro-Soviet, Arabs vs. Israelis and conservatives vs. radicals.

4- In the continued absence of comprehensive peace in the Middle East, do you think real arms control has a shot in this conflict-ridden region? Or do you subscribe to the theory of peace first, then arms control?

I think that a comprehensive peace between Arabs and Israelis would be ENORMOUSLY helpful to arms control efforts in the region, but I am pessimistic that that is a near-term prospect and I think it would be a huge mistake to simply throw up our hands and say that arms control efforts are impossible until there is peace. I have concentrated my writing on this score on the Gulf because I think that the Gulf could make tremendous progress on arms control regardless of what does or doesn’t happen with the Arab-Israeli issue because, frankly, none of the Gulf States really cares much about the threat from Israel, INCLUDING the Iranians. As I have written in this new report and in prior pieces on the subject, all of the Gulf states see one another as their primary security threats and partners, and for all of them, Israel is distant if not irrelevant. Getting serious arms control in the Gulf is going to be very hard, but not because of anything connected to the Arab-Israeli dispute. Beyond that, there is work that could be done among the Arab-Israeli confrontation states BUT (and this is a big but) only if the Arabs can stop trying to use arms control talks to try to get the Israelis to give up their nuclear arsenal. The Israelis are not going to give up their nuclear arsenal—certainly not before a comprehensive peace, but possibly not ever. Arms control could be incredibly helpful to all of the confrontation states (especially Syria, once there is a unified, stable Syrian state again) and if the Arab states were smart, they would try to secure those very tangible and helpful benefits rather than cutting off their noses to spite their faces the way that the Egyptians did by blowing up the ACRS talks by trying to use them to get the Israelis to give up their nuclear arsenal. A pair of pliers is an incredibly useful tool, one that can solve lots of problems; but if you try to use it as a hammer, you are not only not going to drive home any nails, you’re going to break your pliers so that you can’t use them to solve your other problems. That has been the Arab approach to arms control and it is foolish. It doesn’t hurt the Israelis. It only hurts the Arabs themselves.

5- A conference on a Middle East zone free of WMD is scheduled for December 2012. Nobody anticipates major breakthroughs and it is not even clear that the event will take place on time. But if it does, and all regional countries including Iran and Israel decide to participate, what can one realistically expect from this conference? How should the United States approach the conference?

I think the most one can expect from such a conference would be a very mild, aspirational statement that it would be great to someday have a Middle East free of WMD. That won’t seem like much at all, but if you can get that, it will force both Israelis and Iranians (and everyone else) to start to think that that will someday be the goal. That will change things in important ways. Before Camp David and Oslo, there were many Israelis who believed that it was realistic for them to hold on to all of the land that Israel had conquered in 1967. The debate in Israel was between those who knew that they would have to give it back (and the only questions were when and how) and those who wanted to keep it all. That was a very real debate in Israel. Camp David and Oslo—partial and imperfect as they were—demonstrated to all Israelis, that there just isn’t an option to keep all of the land conquered in 1967, and so the debate in Israel has become all about how and when (and how much of) the land is going to be given back. That is a huge shift in the Israeli political debate and that has moved us a LOT closer to real peace than we were in the 1970s or even the 1980s. So that kind of a statement—vague and intangible as it may be—could still be very helpful in changing people’s perspectives, which can eventually change the terms of the political debate.

These are all weaknesses in th

Richard! Does Aussie Dave know

Postol's latest publication ab

Mr. Rubin, I am curious if you

Thank you Uzi. You have obviou

Bruce came back to CSTPV's 20t

Bruce came back to CSTPV's 20t

Thanks for publishing in detai

The 'deal' also leaves Israel

I think that Geneva Talks pose