Interview with Sitki Egeli on Syrian-Turkish incident

July 8, 2012

By Bilal Y. Saab – The incident of the downed Turkish jet by Syria’s military a couple of weeks ago continues to raise important questions. I think we have yet to fully uncover the real security and political implications of that event. Furthermore, despite increasing news reports and (perhaps because of) official statements by Damascus and Ankara, we are still not 100% sure what really happened, given the almost opposite narratives by the Syrian and Turkish authorities. My suspicion has always been that the mission of that Turkish jet, regardless how long it was flying in Syrian airspace, was twofold: take as many photos of Syrian military infrastructure as possible and perhaps more importantly test command and control of Syria’s armed forces (in addition to testing the nature of its air defenses’ responses and the coverage of its radars).

Sitki Egeli, one of Turkey’s sharpest defense analysts, writes independently on various security and military topics, including air power, weapons of mass destruction, nonproliferation, and missile defense. Dr. Egeli holds a Ph.D. in International Relations from Bilkent University and he is the former Director for International Affairs of Turkey’s Defense Industry and Procurement Agency. He currently works at an international defense consulting firm in Ankara, Turkey. I first met Sitki earlier this year in Lake Como, Italy during a workshop sponsored by the Italian Foreign Ministry on the technical details of a WMD-free zone in the Middle East. We hit it off right from the start. His comments during the discussions were spot on and his extensive knowledge of military affairs is quite impressive. The following interview I did with Sitki is intended to shed more light on the puzzle of the Syrian-Turkish military encounter; hopefully it clarifies some important, unresolved issues in the story.

1- What kind of Turkish jet was downed by the Syrian military? It seems like there are conflicting reports out there on this issue.

Indeed, some inaccurate and misleading accounts on the type and capabilities of the jet have surfaced. For example, some claimed that it was a variant of F-4 fighter used to suppress enemy air defenses, implying an offensive or provocative mission. This is simply wrong. Some perhaps confused RF-4 with F-4G variant, which has never entered Turkish service and was used exclusively by USAF.

Now, to set the record straight, the Turkish aircraft that was shot down was a US-built RF-4E, which happens to be photographic reconnaissance variant of the venerable, Vietnam-era Phantom jets. It joined the Turkish Air Force in 1980 and was one of the 18 surviving examples still flying after 3 decades in service. More recently, Turkish RF-4Es including this one had gone through a limited upgrade to keep them flying for another decade. This saw relatively modern navigation, communication and electronic self-protection systems added to the aircraft.

2- Please explain to us its capabilities. What is the typical mission of those kinds of jets?

At least in theory, RF-4E retains a lot of the capabilities present in F-4 fighter-bombers. But this is deceiving. The machine gun to be found in regular F-4s is replaced with a camera bay, and RF-4’s modified radar does not allow firing of the more advanced, longer- range missiles. Therefore, unless there is an emergency, RF-4s do not carry weapons and do not perform armed missions. Their mission payload is confined to an array of day and night cameras used to take snapshots of points of interest. Remember the famous photos of Soviet ballistic missiles to have triggered the Cuban missile crisis some 50 years ago? Those are exactly the type of photos captured and this is typically the sort of mission flown by RF-4E. In other words, very high-speed runs over or near the area of interest, typically at very low altitude to avoid detection by radars and SAM batteries.

But, I am puzzled with one aspect here. Turkish RF-4E can also carry under wing pods housing cameras with much longer-ranges, hence no need to get dangerously close to Syrian territory. Same mission could have been performed by staying well beyond Syrian territorial waters. So, perhaps the Turkish account is accurate and the aircraft was not on a reconnaissance mission, but was testing the coverage of Turkish air surveillance radar to the north. Or perhaps by flying very close to the Syrian coastline, RF-4 was trying to incite Syrian air defense radars and systems in order to reveal their order of battle and to identify their electronic signatures. Or perhaps another as yet unknown mission. This aspect is up to speculation and would probably not be known for a long time to come, if ever.

Now, one more note on the capabilities of RF-4E in question. Besides cameras, the aircraft was fitted with radar warning receivers (RWR). What the latter does is to warn the pilots when their aircraft is “illuminated” by “hostile” radar. The device gives further warning if tracking radar found on surface-to-air missile (SAM) batteries locks on the aircraft, implying that launching of a surface-to-air missile is imminent or has already taken place. The pilots would then change course and altitude, initiate evasive maneuvers, or they can deploy passive defensive aids such as chaff to fool radars. This is a basic electronic self-protection device to be found on most if not all fighter aircraft since Vietnam War years.

3- What do we know about enemy fire? Was it a Surface to Air Missile (SAM) or Anti-Aircraft Artillery?

Whether it was a SAM or anti-aircraft artillery to have shot down the RF-4E is hotly contested between Turkish and Syrian authorities. The Syrian side claims the aircraft was brought down using anti-aircraft artillery, implying it was flying very close to the shore, because effective range of such barreled weapons is hardly more than 2 NM (nautical miles) – well below Syria’s 12 NM territorial waters.

Conversely, Turkish military contends that RF-4E was hit on the edge of Syrian territorial waters. It then went out of control and crashed some 8,5 NM off the coast. Therefore, a SAM offering longer ranges must have been used. Yet, Turkish authorities also admit that no electromagnetic emission coming from SAM batteries was detected during the incident; thence, they claimed, a laser or infrared guided SAM must have been used. What was the basis of this claim? Remember this radar warning receiver installed on the aircraft? Given the existence of such device, if the aircraft was targeted and shot down by a radar guided missile, then its crew would knew that a missile was approaching and would have 30 seconds or more to inform their superiors that they came under attack. This did not happen. So, either a missile using another means of guidance (laser, infrared, CLOS etc) was used and pilots had no warning, or RF-4 was much closer to the shore and fell prey to anti-aircraft artillery.

Yet, claims based on a Sam using laser or infrared guidance hit another stumbling block: there are no known SAMs of such guidance mode in Syrian inventory to achieve a kill at such range (+12 NM). The closest candidate, SA-22 of Russian-supplied Pantsir air defense system (picture above), could have reached 10 NM at most, and some sort of radar cueing still being necessary to initiate the engagement sequence.

Please be warned that a lot of details are still sketchy, thus highly speculative. All those conclusions and judgments may have to be revised as the details continue to surface. Accounts of other parties, such the images that must have been obtained by the powerful British radars in Cyprus, may shed further light on what actually happened.

4- Is Syrian president Bashar Assad telling the truth when he says that he wished his military had not fired on the jet and that they did not know it was Turkish? What does that say about Syrian command and control?

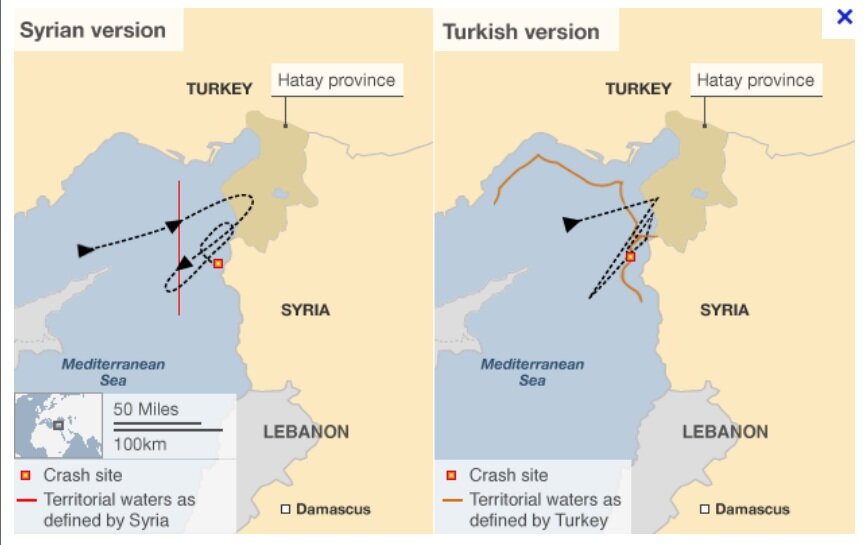

Aircraft’s track information captured by Turkish radars (identical to Syrian version till the last 60 seconds) and publicized by Turkish authorities (see map) holds a number of interesting clues.

First of all, RF-4E was flying in the immediate vicinity of Syria for at least 40 minutes prior to meeting its fate. Thus, it is hard to believe Bashar Assad’s statement that the Syrians did not know this was a Turkish plane. Unless of course, Syria’s air defense command chain is truly dysfunctional or severely stricken, which I don’t find very plausible. Besides, the Turkish transport plane that reached the area shortly afterwards to search for the wreckage was also fired at, which further weakens Syrian claims that they could not identify those aircraft.

Second, 15 minutes before being shot at, RF-4E had violated Syrian air space for roughly 5 minutes and flew a south to north course parallel to Syrian coastline and at very low altitude (100 ft!). When it reached the Turkish coast, it turned around and began flying north-south in a course parallel to the previous run, but this time at a higher altitude and on the edge of Syrian territorial waters. When it reached the point where it had begun its previous violation, either it was shot down and drifted towards the coast before plunging into the sea, or it turned towards Syrian shores to repeat its previous run, but entered within effective range of Syrian anti-aircraft guns already alarmed to the presence of a low-flying aircraft and waiting with fingers on trigger.

I would presume that during the first violation, Syrian air defense crews closest to RF-4E must have contacted their superiors one level up (command center at Homs, Turkish authorities suggested), and asked for instructions. Probably, they have been told to shoot if the aircraft came back and entered within their range. And they simply followed their instructions!

5- How do you assess the performance of Syria’s air defense network? Is it as potent as many think it is? Can’t the U.S. Air Force and NATO jets fly over Syrian airspace, destroy the key nodes, and try not to get hit?

For sure, they managed to bring down a high-speed, low-flying western plane belonging to a well-trained NATO air force. Whether this was a centrally controlled act following clear instructions from the top is difficult to judge. Such airspace incursions take place on a routine basis in the region, over the skies of Cyprus, Aegean littoral or even Syrian-Turkish border. But, no one had resorted to such an extreme reaction of pulling the trigger and shooting down without any warning. Except, of course, back in the 1990s when Syria again shot down a Turkish civilian mapping aircraft inside Turkish air space! That one had turned out to be a case of miscommunication between Syrian pilot and his ground controller.

In case of the more recent incident, the normal procedure would have been for Damascus to issue a diplomatic note of protest and warning (e.g., don’t continue with such incursions, or I will take necessary action). Or perhaps, the Syrian air force could have scrambled a few fighters to force the intruder out. Or under worst circumstances, perhaps few warning shots with tracers by the nearest coastal battery. But, definitely not a shoot-to-kill engagement without warning! Perhaps the instructions were given to Syrian air defense elements to fire at any western aircraft that came close to Syrian airspace – to signal the regime’s determination to resist any foreign intervention or creation of a buffer zone etc. Conversely, if there were no such orders, then this incidence may as well imply poor training, low degree of professionalism or perhaps over-the-edge psychology of Syrian air defense forces.

For one thing, by virtue of Soviet/Russian-supplied and upgraded air defense weaponry in Syria’s disposal, as well as the more organized and robust nature of Syrian military, no one should expect something similar to the catastrophic failure of Libyan air defenses. On the other hand, it would be very naive to expect that in the event of a major conflict or intervention, US and NATO fighters would be flying into Syrian air space before Syrian air defenses are effectively neutralized by information and electronic warfare techniques, cruise missile and stealth aircraft strikes, against which Syria’s old-fashioned and rapidly aging air defense network would simply become irrelevant.

These maps are provided by Dr. Egeli. They show the Syrian and Turkish versions of the incident as well as the jet’s mission profile, as explained by Turkey (the blue map).

Stay Connected: