The General Assembly vote on Palestinian observer status

By Jason Petrucci – It is extremely difficult to hold both substantive and humane views regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It is certainly more intuitive to simply take a side.

Take the recent violence between Israel and Hamas, which touched not only the Gaza Strip but also Israel’s largest cities: Israel supporters typically focus on Hamas rocket attacks launched in peacetime while declining to broadcast any opinions about the total blockade of a population the size of Manhattan or Israel’s continued construction of settlements in West Bank lands they have never made legal claim to; many Palestine sympathizers focus on the hundreds of Palestinians killed every time the IDF undertakes a major operation in the Territories, thereby claiming disproportionality in the use of violence–which implies, whether they admit to this or not, that months of prior attacks by Hamas with the express purpose of killing Israeli civilians (or Hamas’ strategic decision to hide in dense civilian neighborhoods) are morally and politically irrelevant in Israel’s decision to resort to violence. There are the positive neutrals (“I hope that both parties are able to bring this conflict to a quick and peaceful resolution”) whom are of course well-represented in the diplomatic corps, and the negative neutrals (“I wish these idiots would just blow each other up already”) of whom the reader may know a few from private conversation.

Israel drags its feet over giving Palestinians more control over their land and their government, and making reasonable restitution for Palestinian land, property and life lost after taking the upper hand in multiple wars. On the other hand, there has been little discussion among Palestinian sympathizers of the harm done to the Palestinian cause by militants. (Apparently the non-violence that worked for India, Black Americans in the South and Black Africans in South Africa would just never work for Palestinians in the Territories or abroad…But then, the Territories have been under occupation for 45 years and armed struggle has episodically spoiled proposed improvements in their status.) For my part, I share the positive neutrals’ relief to see the violence stop, but I increasingly suspect that these episodes are part of a perverse political negotiation in which some of the parties are foreign and non-public. (A certain Islamic Republic comes to mind, and if I am right it definitely isn’t helping.) I share nothing of the negative neutrals’ animus in this case, aside from a mistrust of many of the powers that be–especially Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s governing coalition and Hamas.

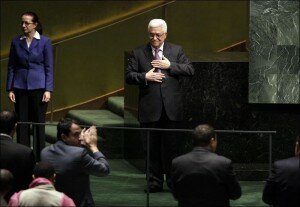

At the end of November the United Nations General Assembly granted Observer status to the Palestinian Authority. Acceptance of the Palestinian Authority’s bid for recognition from the General Assembly was widely anticipated. While this vote does not make the Palestinian Authority a full member in the UN and certainly does nothing substantive to make Palestine a functional state–full membership would have to be granted by the Security Council where the United States wields veto, and Palestinian functional statehood is unattainable without consent from the State of Israel–this vote represents the consensus of the General Assembly and would allow the Palestinian Authority access to a number of United Nations institutions–including, potentially, the International Criminal Court.

The International Criminal Court was organized to deal with charges of war crimes against individual persons. The danger of the Court (and the reason the United States is not a party to it) is that charges of war crimes might be issued on an inconsistent or politically-motivated basis. Now that the Palestinian Authority gains Observer status at the UN, if it is granted access to the ICC it could bring charges of war crimes against IDF or Israeli government officials. The United Kingdom, which ultimately abstained from the vote, had indicated that possible participation in the ICC was one of its greatest reservations against granting observer status to the Palestinian Authority.

I for one applauded the Palestinian Authority’s decision to pursue this acknowledgment from the United Nations, and felt congratulations was owed Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas on its success. While my country and Israel both insist that nationhood can only be granted through negotiations between the State of Israel and the Palestinian Authority, in retrospect negotiations have effectively been frozen since the fall of the moderate Olmert government. (Intransigence from the far-right Likud government is a major culprit, of course, but following former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s controversial withdrawal from multiple settlements in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, Israel has not committed to any further concessions.)

The simple fact is that Israel is taking advantage of the current situation. As I have argued before: This is Netanyahu’s fault for dragging his feet, period. Both his aggressive expansion of settlements in territory with a contested status and his own rationale for not negotiating with the divided Palestinians suggest he never had any intention of granting Palestinians further rights or self-determination. The sad fruits of non-action on the political status of the Palestinians—namely, the on-again, off-again flare-ups of violence with militant groups that can fire rockets deep into Israel—reaffirms why you must negotiate in politics–yes, even with your enemies.

Again, to head-off the skeptics and the shruggers with all their damned reasonable arguments: This step certainly wasn’t full recognition, let-alone functional statehood or a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian dispute, but fair play to the Palestinian Authority for peacefully asserting Palestinians’ rights.

Prime Minister Netanyahu’s (and Likud’s) position remains that the Palestinian Authority must be unitary, accept Israel’s right to exist and renounce violence before the State of Israel will enter any new negotiations. (These conditions sound reasonable until one considers how many wars could never end if they were offered as preconditions for just talking.) Fatah in the West Bank has met these conditions while Hamas has not. When Hamas won a majority in the Palestinian Parliament in the 2006 elections, Israel cut off all the tax revenues it was collecting on the behalf of the Palestinian Authority. This led to a brief but decisive civil war (if we may call it that) between Fatah and Hamas, resulting in 2 separate semi-state entities in the West Bank and Gaza. The Israeli government of Ariel Sharon may have felt it had no choice but to deny revenues to Hamas, but now the Netanyahu government refuses any negotiations with the Palestinian Authority because it “will not renounce violence.” This is a fraud; Likud is just using the Palestinians’ internal divisions as a convenient excuse to leave them in legal limbo.

The Territories have been under military occupation for 45 years. This would be a tragedy if there weren’t a short list of Israeli, Palestinian and Iranian government officials we can hold morally responsible for it. The idea that “the Palestinians” must assume all moral responsibility for this state of affairs, while Netanyahu’s coalition government (which includes public figures, such as Avigdor Lieberman, who would never rise to such prominence in the American political system) builds and maintains new settlements in the West Bank at will, is offered in such bad faith that I suspect its aim is to maintain this situation of perpetual military occupation, in the vague and fantastic hope that over 4,260,000 Palestinian nationals will just…well, go away.

No, I am absolutely not implying what you might be thinking. We should not give quarter to the obtuse and offensive likeness sometimes drawn between the State of Israel and the Nazis. I will be the first to argue that, if its leaders so chose, the State of Israel has the means to do far worse than it has to the Palestinians at any time. But there are limits to the moral as well as the political pertinence of such a point. It in no way changes the fact that the conditions the Palestinians currently abide are awful. If there is a consensus in Israeli politics that Hamas is illegitimate, that doesn’t explain why the State of Israel cannot negotiate further agreements (whether final or interim) with the Palestinian Authority through the agency of Fatah, at least to increase their control over and freedom within the West Bank. But no further agreements have been inked with the faction of Mahmoud Abbas, which has probably wanted meaningful negotiations all along. The real reason Abbas unilaterally pushed for acknowledgment through the UN General Assembly is because his receptivity to Israel has brought him nothing–not even evidence that any further political progress was possible. He was pushed to this point. Our government’s position was that Abbas’ action is “not helpful;” I say, he obtained something for Palestinians and did not have to use violence–indeed, he used a legitimate international mediating institution–to do it. Is there anything intrinsically objectionable about this (unless, perhaps, one wants the Palestinians to have nothing)?

Almost half the West Bank is either under IDF jurisdiction, is reserved for the settlements, has been unilaterally annexed by Israel or has been designated a nature preserve by Israel on the Palestinians’ behalf. Palestinians cannot pass from one side of the West Bank to the other. Palestinians cannot leave the West Bank at all except through Israeli-occupied territory. The State Israel continues to construct new settlements at will, and has built structures on much of the territory with an accessible water table. Note that I haven’t said that the 1967 boundaries are sacred, or that everyone who claims descent from a Palestinian refugee should have a “right of return.” I have only mentioned East Jerusalem implicitly. I have made no argument that the State of Israel is illegitimate in itself, and I am not going to. But in the face of all this, should we expect complete political passivity on the part of the Palestinians and their advocates? Should we accept premises and offer arguments that assume they will be politically-passive? We are supposed to believe that Bibi Netanyahu really just wants peace, and has tragically been frustrated for want of an honest negotiating partner among the Palestinians?

I recognize the State of Israel’s right to exist and its right to defend itself. In everything else it has done, I have long suspected the Netanyahu government of acting in bad faith. Do not forget: In President Obama–whose Ambassador to the UN vetoed a Security Council resolution condemning unilateral settlement expansion, and who voted against granting Palestine Observer status in the General Assembly–Prime Minister Netanyahu sees such an obstacle to the sort of partnership he wants in the United States that in November 2010 met with the incoming Republican House Majority Leader to obtain assurance of more help, and tried to stir-up pre-election controversy to help Republican Presidential candidate Mitt Romney–who had promised him unqualified support.

Observer status for the Palestinian Authority is far from an ideal status (and certainly isn’t the harbinger of the resolution of all outstanding issues)–but it is something. I will not just shrug-off a nonviolent call for legitimate recognition by the Palestinian Authority. If it causes Israel institutional headaches, that marginally increases the political prospect of some kind of concessions, whether negotiated or unilateral. Even incremental progress in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been almost unheard-of since Prime Minister Sharon went into a coma. This minimal level of recognition from the UN General Assembly creates institutional ties that reinforce the concept of and capacity for Palestinian statehood; as I am convinced that Netanyahu has absolutely no intention of allowing Palestinian statehood, this is the first development that improves the prospect of a 2-state solution since Sharon undertook the unilateral withdrawal of West Bank and Gaza settlements.

I don’t think the distinctions I have made here are profound or novel. I do think they are unusual, and require some measure of courage on one’s part, to offer simultaneously. This is because the many unqualified supporters of either side in this conflict have dumbed-down this debate, preferring to speak to the like-minded and invoke their respective cases of victimhood rather than seek help with their own moral blind spots. Taken in isolation these various observations may seem trivial; in combination I think they are worryingly hard to find.

I have not pretended to be an “objective” or “unbiased” observer of these events, or even to know what that is supposed to mean. But I am trying to support the policies (and the prior sentiments) which I consider most-humane. I have often seen no choice on the part of the State of Israel but to use military force against Palestinian militants. This has sometimes earned me consternation from friends who support the Palestinians. On a more-mundane level, or in an event such as recognition of observer status when the Palestinian Authority peacefully seeks further concessions or brings claims against the State of Israel which the latter finds embarrassing or damaging, I find myself referring to the same litany of abuse or neglect which advocates of the Palestinians claim. This seems to puzzle or frustrate friends who support Israel. I only claim a preference for those policies and goals which I think most-humane. The thing I like least is the initiation of violence, the naked use of power (including by a weaker actor); the thing I like next-least is oppression, abusing the advantage of one’s power. I also find invocation of historical grievances useless, especially after generations have passed and the principal victims and perpetrators are dead. We should find it outrageous that there isn’t a serious discussion about the terrorism Hamas regularly perpetrates or attempts against Israel; we should find it outrageous that the Palestinians have had to live under military occupation for 45 years.

We should also find it outrageous that so little passion is contributed to holding both of these views concurrently. I should have more to say about this, but I feel burdened with general claims on which there should be broad agreement but which usually just signal one’s politics.

Jason Petrucci is a former graduate student at the Department of Government and Politics at the University of Maryland, College Park, where he specialized in ethnic conflict, genocide, and civil war.

Powering Lebanon’s grid

By Georges Pierre Sassine – Rolling blackouts have become a symbol of the political crisis affecting the Lebanese government. According to the World Bank, Lebanese citizens incur on average 220 interruptions of electricity per year, which is the worst performance in the Middle East.

Today, electricity production stands at around 1,500 megawatts (MW) while demand exceeds 2,400MW at peak times, resulting in rationing cuts from between 3 to 20 hours a day, depending on where you are in Lebanon. Although the government signed a $360 million deal to lease electricity-generating barges from a Turkish company in July, which is expected to generate 270 MW, this will mainly offset losses as restoration works are carried out on existing power plants.

Building a few facilities to bolster generation capacity should not be too challenging, knowing that China builds plants at the rate of one a month. Instead the problem lies in the sector’s governing system: Lebanon’s electricity sector is dominated by the state-owned Electricite du Liban (EDL), which has thus far proven inept in addressing the country’s energy shortfall.

Moving forward, solutions to Lebanon’s electricity crisis are constrained by a limited government budget, a heavily subsidized electricity sector, low collection of electricity bills, an ageing infrastructure, human resources challenges and various interest groups resisting change.

Politicians are discussing various options, including different models of privatization and even the decentralization of Lebanon’s power generation. The fundamental debate drills down to two key questions. The first is a choice of regulation versus deregulation, which addresses the degree of government involvement in Lebanon’s electricity sector. The second is whether electricity generation should be centralized or decentralized.

These choices are in line with the debates occurring today in the global energy system. As such Lebanese policymakers can learn from the successes of others and adapt them to local conditions.

REGULATION VERSUS DEREGULATION

The electricity sector’s restructuring has featured on the Lebanese government’s agenda since 1998 when a revised electricity law emphasizing privatization was first proposed. Following that an electricity decree was passed by parliament in 2002, more than 60 consultant reports were prepared, and the Council of Ministers adopted different policies in 2002, 2006 and 2010. But very little progress was made on implementing any of these initiatives due to disagreements across the political spectrum around privatization. Some believe that utilities are the business of the government, while others argue for different forms of private sector involvement – spanning from full privatization to various models of public-private partnerships.

The truth is that in Lebanon some form of private sector participation is inevitable. More than 20 percent of the country’s electricity needs are already covered by private generation. Due to crippling public debt, the Lebanese government cannot single-handedly provide the required investment to reform the sector. Complicating matters, any plans to directly privatize EDL would be difficult to implement in the short to medium term, as private investors would be reluctant to invest before operational and managerial capacities are improved.

As Lebanese policymakers continue their deliberations, they seem to be drawing little from other countries’ experiences. The fact is that the electricity industry in many countries has seen a movement from heavy state involvement towards a greater reliance on market processes. The main rationale being that competitive markets raise investments, improve efficiencies and lower electricity prices.

However, the evidence on the success of electricity reform is mixed. In countries such as the UK, Australia, and Chile liberalization reduced electricity prices by as much as 35 percent. Yet, deregulation caused, for example, Sweden’s electricity prices to spike to one of the highest in Europe. The key lesson is that deregulation’s success depends on proper design and implementation of competition laws. Getting market structure right at the opening of new power markets is crucial for the success of any electricity reform; this requires a deep understanding of sophisticated regulation and market dynamics in order to be effective.

Thus, as Lebanese policymakers consider various options for private sector involvement they need to understand the requirements to properly design and implement such a transition. Failure could lead to deteriorating electricity provision and higher prices.

CENTRALIZATION VERSUS DECENTRALIZATION

Another proposal put forward by Lebanese politicians suggests a decentralized electricity sector. The Ministry of Energy and Water would cede control to regions or municipalities. Supporters of such an initiative believe it will help tackle corruption, reduce political bickering and improve governance. However, this raises political sensitivities as some fear that regional electricity production could lead to political decentralization and, in a worst case scenario, to the countries’ undeclared partition.

In a centrally planned system electricity is produced at large generation facilities, transmitted and distributed to thousands and millions of consumers over large geographic areas. It achieves economies of scale, and has been successful in providing consumers with a continuous and reliable flow of electricity. However, today the trend is reversing. Priorities have shifted, and the conditions which created centralized systems no longer hold true.

Renewables and distributed technologies emerged and are becoming more cost competitive, while policymakers’ concerns are increasingly focused on climate change and energy security challenges. This has driven energy planners in the EU and other nations to consider the transition from centralized to decentralized energy systems.

However, decentralized energy systems do not come without their challenges. Technical and engineering challenges abide when integrating large shares of distributed generation into the grid, and could adversely impact the protection and safety of the electric network.

Scoping the map, degrees of decentralization vary from country to country. Brazil has a strong centralized electricity system, whereas Canada’s is decentralized. India and Australia are currently transitioning from a decentralized to centralized structure. There is no unanimity on a universal model. Each provides different benefits and challenges, and need to be assessed within the local context. In Lebanon, however, the motivation behind decentralization remains solely political and fails to account for technical, economic, environmental and energy security dimensions.

In its current form, Lebanon’s electricity sector already has some components of a hybrid centralized and decentralized model. EDL provides only 75 percent of the country’s electricity needs through six large, centrally controlled power plants; while the rest is supplied through a network of small-scale backup generators. The only loophole is that these private generators are technically illegal and as such are not integrated into a wider regulated system.

A pragmatic approach would entail the Lebanese government leveraging the existing infrastructure of private generators across the country and adopting a policy of cooperation and coordination in the medium term, recognizing its inability to fully cover Lebanon’s electricity needs overnight.

In the longer run, a hybrid system combining the best attributes of both the centralized and decentralized structures is possible. It is a matter of finding the appropriate mix that best suits Lebanon and the political will to implement it.

In conclusion, some form of private sector participation in Lebanon’s electricity sector is inevitable under government oversight. But the success of public-private partnerships will be heavily linked to the design and implementation of competition laws. This is particularly pertinent in Lebanon considering existing draft anti-trust and competition laws have been left unimplemented for years on government shelves.

A realistic approach would also require the government to synchronize and leverage existing private generators.

This is a stopgap solution until the most suitable mix of central and decentralized structure for Lebanon is agreed upon. However, this proposal and any other attempt to reform Lebanon’s electricity sector can only be meaningful in the presence of strong political will.

Georges Pierre Sassine is an energy policy expert and holds a master’s degree in public policy from Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. He writes about Lebanon’s public policy issues at www.georgessassine.com

A version of this article appeared in the December 2012 print edition of Executive Magazine, on pages 78 & 80.

Iran’s legal stance on a WMD-free Middle East

By Ariane Tabatabai − The recent postponement of the conference on a Weapons of Mass Destruction-Free Zone in the Middle East (MEWMDFZ) came as no surprise to most observers. Regardless whether one is a pessimist or an optimist, or somewhere in between, the news provides a good excuse to continue to reflect on all dimensions of the topic. Among the many questions that come to mind is that of the role of individual states in the process. In this short piece, I focus on Iran’s.

To better understand Iran’s ambivalent relationship with the concept of a MEWMDFZ, one must first explain the Islamic Republic’s relationship with international law, the nonproliferation regime, and by extension, the NPT.

Since its inception in 1979, the Islamic Republic has criticized the modern international legal framework and its supporting institutions. This has played and probably will continue to play a key role in the way the country approaches diplomacy and the settlement of disputes in accordance with international law. To borrow Allan Gotlieb’s words, ‘there is an obvious relationship between a country’s attitude towards what the law is and its willingness to settle disputes according to that law.’[1] The Islamic Republic has time and time again demonized the international legal system and undermined it, condemning it as a mere tool to subjugate the majority of the world population to a handful of ‘arrogant powers.’ In the words of the country’s highest power, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei:

International peace and security is one of the sensitive issues of today’s world and the disarmament of catastrophic weapons of mass destruction, a pressing necessity and a general demand. In today’s world, security is a common and indiscriminable phenomenon. Those who stockpile their inhumane weapons in their arsenal do not have the right to consider themselves as the flag bearers of international security. This, without a doubt, will not bring them security. Today, it is with a lot of regret that it is witnessed that the countries that have the largest nuclear arsenals do not have a serious and real motivation to remove these deathly tools from their military doctrines and continue to see them as an element of dissuasion and an important factor in their political and international status. This image is completely outdated and obsolete.[2]

Such statements are especially aimed at the five nuclear weapons states who hold veto power at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), a body that the Iranian leadership sees as biased and controlled by the ‘great powers’ since the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq War. Hence, UNSC Resolution 1696, which calls for Iran to suspend all enrichment and reprocessing activities, has been denounced as unjust by various Iranian officials. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the NPT regime are also denounced as discriminatory systems:

The International Atomic Energy Agency is affiliated with the United Nations and was created to supervise the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons. Look at its treatment of countries, its discrimination, the influence of the political constituent in it, because force dominates it.[3]

This attitude toward international law and institutions supports a neo-colonialist ‘enemy’ narrative developed by the Islamic Republic, according to which the world is divided into those who rule and those who are ruled. The first category encompasses the former colonial powers, with the United Kingdom as their flag bearer, the world’s sole superpower, the United States, and Israel. The second category includes the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Muslim world in particular, which Tehran tries to keep on its side. Hence, this attitude toward international law and institutions has become one of the pillars of Iran’s approach to international affairs, yet despite this resilience, one of the key strands in the leadership’s nuclear narrative lies in the fact that its nuclear ambitions are in complete compliance with its international legal obligations and safeguards.

In addition this ambivalent attitude to international law and the world community, Tehran has a puzzling approach to the previous government’s legacy. Indeed, Tehran denounced the Shah (still does) and viewed him as corrupt and dependent on the West. As such, the mullahs try to distance themselves from the Pahlavi dynasty as much as possible and refuse to acknowledge any positive outcome of the previous rulers’ legacy. However, occasionally, the mullahs seem to forget that they represent the Islamic Republic and their referral to the ‘we’ encompasses the previous regime. This has been a particularly interesting ‘slip of the tongue’ in the case of the country’s advocacy for the creation of a WMDFZ in the region.

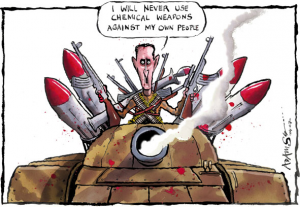

The Islamic Republic of Iran considers the use of chemical and nuclear weapons and the likes a great and unforgiveable sin. We have proposed the slogan of a “Middle East free of nuclear weapons” and we stand by it. This does not mean giving up on the right to use peaceful nuclear energy and the production of nuclear fuel. The peaceful use of this energy, according to international law, is the right of all countries.[4]

In fact, the ‘we’ that proposed the creation of such a free zone along with Egypt was the Imperial State of Iran not the Islamic Republic of Iran. While international law does not distinguish between the two regimes, as they both govern the same nation, such words coming from the Supreme Leader are particularly interesting, as they seem to highlight the nation’s continuous commitment to this process.

Yet, in spite of this seemingly continuous dedication and its adoption of the different nonproliferation instruments, including the NPT, CWC, and BTWC the country has failed to take positive steps toward the materialization of this goal. First, the leadership’s continued demonization of international law and institutions has a negative impact on an already fragile process in the world’s most unstable region. Indeed, such an attitude to globally established norms and institutions does not make a suitable environment for confidence-building and trust, a crucial foundation of such a free zone. Second, the ‘enemy’ narrative is one that should be banished to make room for cooperation if the WMDFZ is to be successfully created in the region. Such a narrative cannot be the basis of regional cooperation. Both these challenges seem extremely difficult to overcome in the context of the current theocratic regime, as the very existence of the Iranian system is based on these two rhetorical strands.

Ariane Tabatabai is a Ph.D. candidate at King’s College, London. Her dissertation examines the strategic implications of the legality of nuclear weapons under Sharia law.

[1] Allan Gotlieb, Disarmament and International Law – A Study of the Role of Law in the Disarmament Process, Ontario: The Canadian Institute of International Affairs (1965), PP. 96

[2] ‘Statement in the Sixteenth NAM Summit,’ http://farsi.khamenei.ir/speech-content?id=20840, 30 September 2012, Translation Ariane Tabatabai, Last accessed 14/11/2012

[3] Majles Research Center (2012), ‘The Stances of the Supreme Leader of the Revolution Regarding Sanctions and the Nuclear Diplomacy of the Islamic Republic of Iran,’ PP. 17

[4] ‘Statement in the Sixteenth NAM Summit’. http://farsi.khamenei.ir/speech-content?id=20840. 30 September 2012

Obama’s Syria red line

By Bilal Y. Saab – Syria’s military has once again moved its chemical weapons. Last time this happened, worries that chemical attacks on rebels or the civilian population were imminent ended up being unfounded. This time, American and Israeli officials are saying that the movement is “a kind of action we’ve never seen before” and “suggests some potential chemical weapon preparation.” This prompted another round of vague warnings by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that using chemical weapons would cross a “red line” and that America would “take action,” a reiteration of remarks made three times over the past year by President Obama.

Obama’s red line on Syria is worth scrutinizing closely because it provides insights into the haphazard nature of the administration’s overall Syria policy. The curious logic and poor credibility of Obama’s threat are somewhat interrelated. Why has the United States drawn a red line here and not elsewhere?

Obama’s words could reflect a humanitarian concern and a moral responsibility to prevent the further loss of life in Syria. Yet the president has not reacted forcefully to the tens of thousands who have already perished without a single poison being used. Chemical weapons are considered weapons of mass destruction, and if used effectively, could kill in the thousands. But so can fighter jets, helicopters, tanks and artillery—and they already have.

What if Assad never uses toxic assets throughout this conflict but continues to methodically bombard and kill on a daily basis? Or what if he uses small quantities of those weapons and ends up killing fewer people than his daily average, would the red line still apply? From a purely moral or humanitarian standpoint, Obama’s equation does not make sense. How could constant, lethal and inhumane conventional bombardments be considered fair game while one class of weapons, no matter how it is used, is unacceptable?

If the usage of chemical weapons is considered as grave and game changing from a U.S. standpoint, how does Obama rank the following scenarios, which are likely worse?

- -A civil war that massively spills over to Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Turkey, igniting similar civil wars in one or two of those countries and threatening key U.S. allies.

- -A war between Syria and Turkey following repeated military skirmishes along the borders.

- -An Al-Qaeda movement that succeeds in establishing a solid base in Syria.

Surely these scenarios pose worse consequences than Assad using or moving chemical weapons.

Despite Obama’s repetition, his red line on Syria lacks credibility. There is no reason to doubt that this president means what he says, but the problem is that what he said was anything but clear. Assad might either misunderstand it or dismiss it.

Some would argue that Obama did not need to specifically mention that the United States would intervene militarily—such vagueness is good because it keeps his opponent guessing. They would add that it is unnecessary for Obama to corner himself by issuing a specific threat which he could be forced to execute. Surely Assad must understand what Obama is referring to when the latter says that he would “change his approach so far.” Presumably Assad learned after the debate on Iran sanctions that Obama doesn’t bluff.

In reality, ambiguity undermines credibility. It has been almost two years since the Syrian uprising began, and no one has been able to stop Assad from killing thousands of people and destabilizing his neighbors. Western tolerance of such a high death toll in Syria (currently pushing forty thousand) has probably made Assad think that he has a virtual green light to continue with the killing. So why would the use of chemical weapons change anything, Assad might wonder, especially if the Syrian leader uses them in small and possibly undetectable quantities? Assad might be thinking that Obama didn’t utter the words “military intervention” or “use of force” because he could not follow through on his threat.

Now that he is reelected, Obama will have more latitude in international affairs and fewer worries about the domestic political consequences of his foreign policies. But that does not mean that he will all of a sudden have fewer qualms about military intervention in Syria. Obama was and still is genuinely concerned that in a combustible region, an attack against Syria, no matter how surgical, would spiral out of control. This could cause a widespread conflagration that would involve Israel, Iran, Hezbollah, and Hamas. What would start as a limited military operation meant to stop the bloodshed, remove the dictator, and secure a large chemical arsenal could end up with severe unintended consequences: more people dying, a scattered chemical arsenal that ends up in terrorist hands and a heavily contaminated Syrian atmosphere. Syria is a chemical powder keg.

Yet even if Obama enhances the credibility of his threat and adds specificity to his red line, it is not clear that it will matter. The last thing Assad needs in his existential war against his people is NATO fighter jets flying over Damascus and bombing his palace. The Syrian army is already stretched too thin and Assad cannot afford to redirect some, if not all, of his military resources to combating a much more powerful U.S.-led NATO force.

But what if Assad finds himself facing the fall of Damascus? Given his uncompromising behavior so far in the conflict, it is possible that Assad will fight until the end and use whatever assets he has at his disposal, including chemical weapons, to prevent total defeat. Assad might prefer to deal a decisive blow to an imminent threat now and worry about confronting a Western intervention later. Assad is not powerless if he has to face a NATO onslaught, and he can rely on his Russian-supplied air defense systems as well as his extensive chemical arsenal, which the foreign ministry recently mentioned could be used against foreign invaders.

There may be nothing that Obama could say that would change Assad’s calculations or the course of the conflict in Syria. But we are not dealing with absolutes here. To deter Assad from escalating and using chemical weapons, Obama must not only issue a more credible and specific threat. He must also overhaul his approach to Syria. The current red line is insufficient because its foundation is a weak policy and a questionable presidential commitment to Syria. The deterrent threat should be proactive—not reactive as it is now—and center on denial rather than punishment.

A more active and coherent Syria policy, of which the red line is only one part, is desperately needed. It should start with a program to work with U.S. allies to vet, train, and arm the Syrian rebels. This is what the CIA is for, but the Turks and the Jordanians should be at the forefront of the effort given the close links they already have with the rebels. It is critical for the United States to have a friendly constituency in Syria, not only to secure Assad’s toxic assets but also to deal with a host of other contingencies the day after the dictator is gone. America has no friends in Syria. This must change, and fast.

This analysis first appeared in The National Interest on December 04, 2012 and is being re-posted here.

These are all weaknesses in th

Richard! Does Aussie Dave know

Postol's latest publication ab

Mr. Rubin, I am curious if you

Thank you Uzi. You have obviou

Bruce came back to CSTPV's 20t

Bruce came back to CSTPV's 20t

Thanks for publishing in detai

The 'deal' also leaves Israel

I think that Geneva Talks pose