An early look at the Iran-EU-5+1 Joint Action Plan

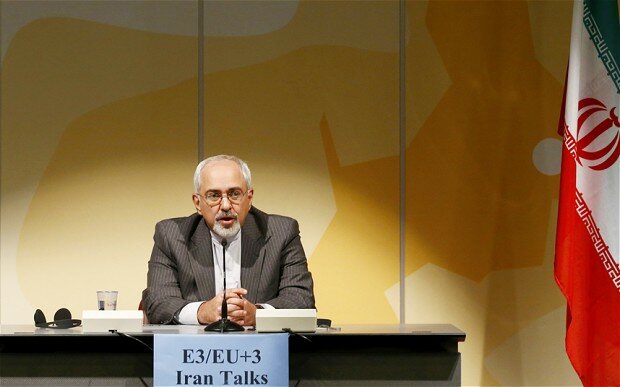

By Miles A. Pomper – The P5+1 (the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France, Russia, and China, facilitated by the European Union) agreed with Iran on November 24, 2013 in Geneva on a six-month Joint Action Plan. The agreement is supposed to serve as an interim deal, setting the stage for negotiations over a longer term, comprehensive agreement. Below are three sets of observations related to the interim agreement, the forthcoming negotiations over a potential long term deal, and the less –discussed period after such a long term deal would have run its course.

The short term:

The provisions on the known parts of the Iran program are sufficient and likely worth the apparent price of sanctions relief, probably buying several months of respite from an Iranian move to a bomb (how much exactly depends in part on your estimate of how much of installed but not currently running centrifuges Iran would have activated in the meantime). This is true even if this is a solution we could have had 8-10 years ago if the Bush administration had been willing to engage with the EU negotiations at that time.

Some lesser-noticed provisions, such as use of daily camera runs at the current enrichment plant (as opposed to weekly or biweekly now) may play as much a role as the more-ballyhooed restrictions over enrichment levels. In part, this will depend on how seriously the U.S. enforces other sanctions in the meantime to keep indirect costs from sanctions leakage to a minimum. It also depends on how you count the P5 +1 pledge not to further cut Iran’s oil sales in the period below current low levels (how much would they have been cut?) and exactly how much higher EU thresholds on non-sanctioned trade will be raised relative to the status quo.

A central concern is the implication that this agreement may be the final one, not an interim one. Given the fact Iran and the U.S. will find it much harder to reach a final deal in six months we will probably face the choice of paying Iran another effective bribe to continue this agreement or risk another slide toward a war.

The interim agreement could have been more effective with additional IAEA access to ensure that Iran does not have clandestine facilities (i.e. have a so-called IAEA additional protocol to their safeguards agreement in force or at least as Tehran did from 2003-2005 acting as if such an agreement were in force). There are some provisions that are reassuring on this front including monitoring of centrifuge production (which would make it hard to construct new plants), and Iranian agreement not to establish other enrichment plants. That should make it harder and at least a violation of the agreement for Iran to establish new clandestine facilities. So we can either hope Iran does not have already such facilities or that it will hide and not use them for the next six months. It can be anticipated that disputes over whether such facilities exist will pop up in the next months and may derail the interim or final agreement.

In addition one provision in the agreement “the U.S administration, acting consistent with the respective roles of the President and the Congress, will refrain from imposing new nuclear-related sanctions,” may prove problematic with Congress and many on Capitol Hill will be tempted to throw a spanner in the works. Recent comments by Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Menendez may offer a way out—passing new sanctions legislation but essentially deferring implementation if the interim agreement is carried out and a final deal agreed upon. But the language here—and how it is interpreted by the Iranians—could be crucial.

The medium term:

The short term agreement states that the parties envision a long-term agreement that would “comprehensively lift U.N. Security Council, multilateral and national nuclear-related sanctions, including steps on access in areas of trade, technology, finance, and energy, on a schedule to be agreed upon.” In return, Iran would agree to limitations on its program, ie. “a mutually defined enrichment program with mutually agreed parameters consistent with practical needs, with agreed limits on scope and level of enrichment activities, capacity, where it is carried out, and stocks of enriched uranium, for a period to be agreed upon.” Iran also committed to ratifying an agreement allowing an additional protocol—i.e granting the IAEA ability to search for potential clandestine facilities and providing other measures of transparency.

The agreement sets a goal of agreeing upon and commencing implementation of a longer-term agreement within a year. This is likely to be where things get truly sticky. My assessment is that the U.S. and Iran will not be able to agree by the six months mark and when we get close to the one year mark the Iranians will announce they are not ready to negotiate another short-term deal and want a long term solution.

That leads to three main issues in negotiating the comprehensive agreement within six months to a year:

- What will be the agreed parameters on the enrichment program?

- What is the sequencing of relaxing sanctions vis restrictions on enrichment and IAEA inspections?

- And I think this is the most problematic and least noticed issue, how long is this period of restrictions supposed to last? Presumably we will want this to last as long as possible and the Iranians will want this as short as possible.

Long-term questions/concerns:

The agreement says that “Following successful implementation of the final step of the comprehensive solution for its full duration, the Iranian nuclear program will be treated in the same manner as that of any non–nuclear weapon state party to the NPT.”

That means that once the duration of the period for the enrichment restrictions ends under the long term agreement, assuming Iran has taken all the other steps it has pledged to take, it will have no restrictions on its enrichment program and no sanctions. The notion that the long term agreement would lead to a PERMANENT restriction on Iran’s enrichment program is simply wrong; longer-term restrictions, perhaps, but certainly not permanent.

That means that at some point, Iran could revert to having an enrichment capability that would put them on the cusp of acquiring a nuclear weapon, although with greater transparency through the IAEA additional protocol, and perhaps more information about their past weaponization efforts. The issue of past weaponization efforts has been fudged in the interim agreement.

This leads to a final set of questions and concerns:

First, can Congress (let alone Israel and Saudi Arabia) live with the uncertainty and lack of leverage over Iran’s program that such a long term agreement might generate? On the other hand, how will it play in the international arena if Iran has shown a willingness to comply with all of the steps required in the agreement but Congress block its implementation by refusing to lift sanctions. It will be hard for U.S policymakers to defend Congress’s action if it is simply Congressional distrust of Tehran rather than specific concerns about specific activities that stand in the way. And if in response to a failure to lift sanctions, Iran walks away from the agreement then, how easy would it be to reimpose sanctions or use military force?

One possible approach might be for Congress to make clear that as a prerequisite and to provide sufficient confidence, Tehran has to resolve satisfactorily the past IAEA questions about Iran’s weaponization activities before a permanent agreement goes forward.

Secondly, the agreement is likely to harm efforts by the US to discourage all U.S nuclear cooperation partners from engaging in enrichment and reprocessing –particularly Saudi Arabia, which even if it doesn’t start such a program soon will certainly want to keep open the option.

Last, one wonders how North Korea will react. At the very least, the agreement may serve as an additional talking point for Pyongyang in arguing why the 1992 denuclearization agreement, intended to ban enrichment and reprocessing on the Korean peninsula, is not valid. Beyond that, the nuclear status of the two countries–and current U.S policy towards them is so dissimilar that it’s hard to speculate on the fallout for Northeast Asia.

Miles A. Pomper is a Senior Research Associate at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies.

How to strengthen the interim Iran deal

By Orde F. Kittrie – While US Secretary of State John Kerry pushes back hard against Senate threats to pass a new Iran sanctions bill, his negotiators are hopefully using that same Senate threat to extract a better deal from Tehran.

Press reports make it clear that the interim deal will bring Iran into compliance with none of its key international legal obligations as spelled out in applicable Security Council resolutions. These resolutions explicitly require Iran to verifiably: “suspend” all enrichment-related activities; “suspend” work on “all heavy water-related projects” including the construction of the Arak heavy water reactor; “provide such access and cooperation as the IAEA requests” to resolve IAEA concerns about Iran’s research into nuclear weapons design; and “not undertake any activity related to ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear weapons.”

It was unrealistic to think that an interim deal would bring Iran into compliance with all of its key preexisting legal obligations. But it seems surprising that Iran is to receive billions of dollars in sanctions relief in exchange for compliance with none of them.

As President Obama said at a press conference, the goal of “this short-term, phase-one deal” is to be “absolutely certain that while we’re talking with the Iranians, they’re not busy advancing their program.” Unfortunately, the draft interim deal, as described in press reports, also falls far short of what the President set as the goal of this phase-one deal.

If the interim deal is to meet President Obama’s declared objective for it, it must include stronger provisions relating to enrichment, Iran’s heavy water reactor at Arak, and Iran’s research into nuclear weapons design.

With regard to enrichment, if the interim agreement is to make “absolutely certain that while we’re talking with the Iranians, they’re not busy advancing their program,” it should include the following provisions additional to those reportedly included in the draft interim agreement: halt all Iranian enrichment; verifiably prohibit Iran from manufacturing additional centrifuges; require Iran to adhere to the Additional Protocol; and require Iran to accept and immediately and verifiably implement its existing legal obligation to notify the IAEA of any enrichment or other nuclear facility it possesses or begins constructing.

The draft interim agreement reportedly fails to require Iran to suspend enrichment of uranium to 3.5 percent. It also reportedly places no constraints on Iran’s continued manufacturing of centrifuges.

The draft interim agreement would thus enable Iran to, at the end of the six month interim agreement period, possess both a larger stockpile of uranium enriched to 3.5 percent and a larger number of manufactured centrifuges than it does today. These advances would put Iran in position to much more quickly produce far more weapons grade uranium than it can today. Tehran would be significantly closer to the point at which it is able to dash to produce enough weapons-grade uranium for one bomb so quickly that the IAEA or a Western intelligence service would be unable to detect the dash until it is over.

Nor, according to press reports, does the draft interim agreement ensure, or even enhance, Western or IAEA ability to detect any covert Iranian enrichment facilities. Estimates of Iran’s proximity to undetectable breakout assume that Iran only has the capacity to enrich uranium in its known sites at Natanz and Fordow, both of which were built by Iran in secret.

The IAEA says Iran has a legal obligation, under modified Code 3.1 of the IAEA-Iran safeguards agreement, to notify the IAEA if Iran begins construction of a nuclear facility, including an enrichment facility. Iran is refusing to comply. An interim agreement should commit Iran to notifying the IAEA of any nuclear facility it begins or possesses.

Iranian adherence to the Additional Protocol would further decrease the risk of a covert Iranian enrichment facility by enhancing the IAEA’s ability to detect and inspect any such covert facilities. The November 2013 IAEA report emphasizes that the IAEA “will not be in a position to provide credible assurance about the absence of undeclared nuclear material and activities in Iran unless and until Iran provides the necessary cooperation with the Agency, including by implementing its Additional Protocol.”

Similarly dangerous gaps are present in the draft interim deal’s handling of Iran’s heavy water reactor at Arak and Iran’s research into nuclear weapons design.

The draft interim deal reportedly includes Iran continuing construction of its heavy water reactor at Arak, while committing to not bring it online for the duration of the six month interim deal period. By continuing construction of the Arak heavy water reactor, even with a commitment not to produce additional fuel assemblies for six months, Iran will continue to advance towards creating plutonium. A senior French official was recently quoted as saying, “As soon as Arak is in operation, Iran can make one nuclear bomb per year, according to our calculations . . . It is absolutely essential that it should not become active and it is essential that it must be frozen as part of any interim accord.”

The only way to make “absolutely certain that while we’re talking with the Iranians, they’re not busy advancing their program” at Arak is for Iran to verifiably halt all construction, as Iran is already required to do by several UN Security Council resolutions.

Meanwhile, the draft interim agreement reportedly does nothing at all to make “absolutely certain that while we’re talking with the Iranians, they’re not busy advancing” their prohibited research into how to design and deliver a nuclear weapon.

IAEA reports have provided extensive information about such Iranian research. In its May 2011 report, the IAEA described documentary evidence of Iranian “studies involving the removal of the conventional high explosive payload from the warhead of the Shahab-3 missile and replacing it with a spherical nuclear payload.”

The November 2011 IAEA report annex provided a more detailed description of information the IAEA determined “indicates that Iran has carried out . . . activities that are relevant to the development of a nuclear explosive device” and noted “indications that some activities relevant to the development of a nuclear explosive device . . . may still be ongoing.”

Unfortunately, neither the draft interim agreement nor the November 11, 2013 Iran/IAEA “Joint Statement on a Framework for Cooperation” provide the IAEA with any additional access or cooperation to make “absolutely certain that while we’re talking with the Iranians, they’re not busy advancing” their prohibited research into how to design and deliver a nuclear weapon.

Unless these gaps are closed, the interim agreement will make absolutely certain that while we’re talking with the Iranians, they will be busy advancing their illicit nuclear program. Less quickly than in the absence of such an agreement, but advancing it nonetheless.

Orde F. Kittrie is a professor of law at Arizona State University and a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. He previously served for ten years at the U.S. State Department, including as lead attorney for nuclear affairs, in which capacity he participating in negotiating several U.S.-Russian nonproliferation agreements. A more detailed version of this analysis is available for download at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2356923.

For America’s Gulf allies, anxiety is not a plan

By Bilal Y. Saab – It is no secret that the Arab Gulf States have a problem with the style and substance of the US diplomatic approach toward Iran (or rapprochement, as viewed from Riyadh, Abu Dhabi and other Arab Gulf capitals). As allies, they feel they should have been consulted prior to Washington “opening up” to a historical foe such as Tehran, and their primary concern is that talks could amount to a nuclear deal that would threaten their security and sanction the emergence of Iran as power broker and policeman of the region.

But Arab Gulf concerns are not limited to the Iran issue, they are rooted in the belief that the Obama administration “simply doesn’t get it and is jeopardizing the alliance,” as one senior Saudi diplomat recently told me. A profound lack of trust currently characterizes relations between the United States and its Gulf allies. “The gulf is there, whether we like it or not,” one UAE former senior official said to me last summer.

Many in the US policymaking community have argued that the Arab Gulf States’ concerns are inflated and do not reflect reality. This line of reasoning, however, serves no useful purpose. While fears and emotions can sometimes be irrational (especially when you are in a vulnerable position), in this case, however, they are hardly baseless. It is highly unlikely that the Obama administration would abandon its Gulf allies in favor of a new relationship with Iran, but it has however mishandled almost every crisis in the Middle East, leaving friends and enemies alike wondering if this is a case of ineptitude or disengagement. With such a poor US policy record, the Arab Gulf States have every reason to worry that by reaching out to Tehran, Washington, not out of malicious intent but out of incompetence, could hurt their interests. Misplaced or not, the Arab Gulf States’ concerns should be addressed with a greater sense of urgency and seriousness for one simple reason: they are America’s allies in a strategically vital and energy-rich region.

As I wrote in the National Interest on June 20, 2013, the most effective antidote to this turbulence in relations is a brutally honest dialogue that addresses the tough policy issues affecting the future of the region and lays out mechanisms for increased cooperation and closer interaction. The two sides will disagree on many things, as they have clearly shown on Syria and Egypt, but differences can be managed and agendas can be brought closer together.

But a crucial question must be asked still: What if greater consultation, for whatever reason, does not produce desired results? This is an issue that should occupy the minds of Arab Gulf leaders. It is one thing for them to communicate their concerns to Washington (and no country has done it more bluntly than Saudi Arabia), but a different thing altogether to actually have a strategy for perceived continued US negligence or passivity. Anxiety is not a plan. As worrying as the current chasm with Washington is, it ironically presents an opportunity for the Arab Gulf States to smartly and carefully re-calibrate their relationship with the United States and adjust their expectations from the alliance. Turkey has done it with NATO, and nobody has vilified it for doing so.

To induce better US cooperation, the Arab Gulf States should first and foremost do a better job of making themselves heard, without making things worse with Washington or appearing like they are employing punitive measures. While Saudi Arabia’s rejection of a seat on the Security Council was loud and shocking, it is not clear if it will achieve the intended objective or benefit the Kingdom. All it does is deny it an influential voice in New York and a greater role in international diplomacy. Arab Gulf leaders’ complaints to their American counterparts have been mostly expressed in closed rooms and on bilateral levels. This is understandable, and there is merit in keeping at least some aspects of the conversation private. However, a collective and public response can also send a stronger message to Washington and immediately grab its attention. A joint statement coming out of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) that is robust but non-confrontational will show that the Arab Gulf States are united in their stand and share the same concerns about US policy in the region.

In the areas of trade and commerce, the Arab Gulf States have some leverage that they can intelligently exercise. While it would be self-defeating for the Arab Gulf States to reduce their level of trade with the United States (which totaled around $100 billion last year) to drive their point home, privileged access to the Arab Gulf market may no longer be granted to the United States. This essentially means that trade with China and other world powers would be boosted, inevitably at the expense of US economic interests.

With regard to defense procurement, the Arab Gulf States might want to further diversify their sources. While US weapons technology is undoubtedly the best in the world, Arab Gulf allies can pay closer attention to what France, India, South Korea, and even China have to offer, as a sign of displeasure with Washington (although issues of interoperability would have to be taken seriously if a decision to complement current arsenals with non-US systems is to be made). Every Arab Gulf penny spent on non-US military hardware is a penny not earned by the United States. Arab Gulf states buy arms from the United States not just to upgrade their defensive capabilities but also to strengthen the US-GCC partnership as a whole. And Washington knows it. If the Arab Gulf States start buying non-US weapons in greater quantities Washington may well come to understand that there is something deeply upsetting in the alliance and that more should be done to ease the worries of Arab Gulf allies.

Again, a more transparent dialogue and better communication between the United States and its Arab Gulf allies might render these proposed short-term actions unnecessary. However, even if trust is restored and regardless what happens on the diplomatic front with Iran, the Arab Gulf States ought to start thinking strategically beyond their US protector. This exercise should have been initiated a long time ago, but better late than never. No country living in an increasingly dangerous neighborhood can solely rely on external protection to ensure security, no matter how powerful and trustworthy the ally is. Also, no status-seeking country can pursue its national interests and aspirations without policies and strategies that are independent from its external ally. Just look at Israel, for example, and how its alliance with the United States – arguably the strongest in the world – has rarely prevented it from pursuing its own interests and engaging in unilateralism, sometimes at the expense of US objectives and interests. Lest there be no confusion: this is not about punishing the United States for falling short with its Gulf allies. It is about the Arab Gulf States rationally pursuing their own interests and taking some matters into their own hands.

A truly unified political and security alliance among GCC states is the best strategic option the Arab Gulf States have for assuming greater self-defense responsibilities in the future. It is also the most potent answer to the challenge of Iran. Indeed, the Arab Gulf States have to realize that together they stand a much better chance of containing Iran, whether or not it reaches a strategic understanding with the United States or acquires a nuclear weapon. Yet this framework also happens to be the most ambitious and difficult to achieve, knowing that at present relations among GCC states are plagued by distrust, petty politics, and rivalry. The ball is in the Arab Gulf States’ court. They can choose to maintain a healthy dose of competition amongst themselves but work much closer together to meet common security goals, or they can continue to go in separate ways and consequently leave themselves more vulnerable vis-à-vis Iran (even though the threat of Iran is not as severe as some Arab Gulf States think).

Despite the current uncertainty in relations between the Arab Gulf States and the United States, I still believe that the bond is too strong to be broken. But even when they kiss and make up, this tempestuous episode should serve as a catalyst for the Arab Gulf States to begin rethinking their future approach toward security because their ally has made it very clear that as it gets closer to being energy independent sometime within the next decade its engagement in that part of the world will further diminish.

Bilal Y. Saab is the Executive Director and Head of Research of the Institute for Near East and Gulf Military Analysis (INEGMA) North America. This article originally appeared in The National Interest on November 18, 2013.

Jordan (not so much) on the brink?

By Jaymes Hall – Jordan opposed the Assad regime in the beginning of the Syrian civil conflict, but has all but fallen silent as the unrest continued. Partly in response to the stalemate in Syria, but perhaps more importantly due to the growth of extremism inside and around Jordan, Amman has reconsidered some of its domestic policies and its overall approach to regional affairs.

Growing extremist role

With memories of the 2005 Amman hotel bombings still vivid in the Jordanian government’s mind, domestic security against extremism has been a focal point for the state’s security interests. When on October 21, 2012 the General Intelligence Directorate (GID) announced it had foiled an Al Qaeda plan to assassinate Western targets and bomb shopping centers with weapons smuggled from Syria, the operation was dubbed a huge success. But it also underscored the growing presence of terrorist elements in the country. While not mutually exclusive, a large number of the extremists have historically come from the Jordanian Salafist communities. Within the Jordanian community the number of Salafists continues to remain significant, figured as high as 5,000 individuals by both Salafist and security forces.

The province of Zarqa, colloquially known as the Salafist haven of Jordan, is a pivotal region where extremism continues to proliferate. As the hometown of Al Qaeda in Iraq’s (AQI) late leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the city has a legacy as a hotbed for unrest. In 2011, over 100 Salafist demonstrators were arrested after a demonstration for the release of 300 imprisoned Salafists became bloody, where over 80 policemen were injured by the Salafists wielding swords, clubs and knives. The crackdown was extensive, but did not deter the groups from continuing opposition activities against the state.

Salafist jihadi elements inside Jordan have called on their followers to travel to Syria in order to wage holy war. Many of these Salafist jihadis have already heeded the call of assisting their Syrian brethren. The accessibility of Syrian rebels to traverse back-and-forth across the Syrian-Jordanian border with relative ease has led to a large number of Jordanian foreign fighters. Approximately, 700 Jordanian citizens are currently engaged in combat across Syria and most are within the ranks of Jabhat al Nusra. The return of these trained and zealous individuals is a major concern comparable to the Mujahedeen of Afghanistan returning to their home countries after the departure of the Soviet Military in 1989. Jordan does not want to see the same scale of violence the Algerian people felt at the mercy of the Mujahedeen based Armed Islamic Group in Algeria during the 1990s.

Saudi Arabia gets busy in Jordan

Saudi Arabia recently shocked the international community when it refused a seat on the UN Security Council. As dramatic as it was, this act is suspected to have been carefully calculated by the Saudi regime to demonstrate their growing engagement in the Syrian conflict. The Kingdom’s involvement in Syria has fueled closer relations with Jordan. However, the relationship has become progressively one-sided toward Saudi Arabia as the conflict rages on.

With a deteriorating security situation in the region, Saudi Arabia’s recent role in Jordan has been providing economic stability. While the economic situation in Jordan was not ideal before the Arab Spring, regional uprisings further exasperated the realities on the ground within the Hashemite Kingdom. Saudi Arabia worried about unrest parallel to its border, began flooding Jordan with aid in an effort to quell some of the burgeoning unrest. In 2011, the Saudi government offered Jordan $1.4 billion to stabilize the economy. This aid has continued into 2013, where the aid is still a staggering $1 billion.

This funding however may have come at the price of Saudi Arabia equipping Syrian militants on Jordanian soil. With arms transfers streaming out of former Yugoslav caches coming in from Croatia to Queen Alia Airport in Jordan, Saudi Arabia has created a precarious situation for the Jordanian regime. Shifting from equipping rebels in the north, Saudi Arabia has been focused heavily on what they call their “Southern Strategy.” With more and more individuals being equipped and trained in tactics to overcome an authoritarian regime, this could create a spillover effect for the Hashemite kingdom, as many of these returning individuals could precipitate further unrest.

Further exasperating the tenuous situation is the lack of regard for the groups being armed by the Saudis. In the past, Saudi Arabia predominately equipped groups merely on the premise that the groups either rivaled those backed by Qatar, or until the recent fissure between Saudi Arabia and the US, the groups designated by US intelligence officials. With the recent gains made by Al Qaeda elements in Syria, Saudi Arabia played a tantamount role in bringing 50 Islamist groups together and forming the “Army of Islam”. Saudi Arabia reportedly forged this alliance under the direction of Intelligence Chief Prince Bandar bin Sultan. Prince Bandar is a controversial Saudi official who was Ambassador to the United States during the 1980s, who lobbied heavily for US and Saudi armament of Mujahedeen in Afghanistan. With this framework in mind, Prince Bandar is making similar mistakes from decades past, still under the impression that Saudi has the ability to control Islamist elements through a common ideological background and ties with their militant leaders. However, these groups much like the Islamist groups of Afghanistan are far less malleable than perceived. The strengthening of these groups may improve the overall military situation of the Syrian rebels, but may decrease the security of Jordan, as it is these ideologically driven Islamists so near its borders, which alarms the regime most.

Jordan adapts

Realizing the myriad of issues beginning to take place within its borders, Amman has taken several steps to consolidate its hold on the state and institute changes reflecting challenges on the ground.

The Jordanian regime has worked to neutralize radical Salafist recruitment through programs set to bring Muslim Brotherhood elements into the government camp. By including these elements into a camp loosely affiliated with the regime, the Jordanian government may redirect these Islamist elements as a counterbalance to radical and Salafist support in the country. The recent launch of the Zamzam Initiative is one such example the government has supported in an attempt to draw more moderate-reformist elements into the regime’s corner. With the Muslim Brotherhood’s recent failure to garner support for the boycott of the Parliamentary elections coupled with the ouster of the Brotherhood from Egypt, many Islamist reformers have begun to see cooperation as the only viable outlet to achieve their goals.

Jordan has also taken a hardline approach towards radical individuals using Jordan as a gateway into the Syrian conflict. Noting the influx of radical Salafists migrating across its borders, Jordan and has taken steps to crack down on such groups. In September Jordanian military courts convicted a dozen jihadists to five year prison sentences for attempting to cross the border and join Jabhat al-Nusra. By cracking down hard on fighters intent on joining extremist groups like Jabhat al-Nusra, Jordan may hope to weaken the future effects these individuals may have on the state when the fighters begin returning home.

Saudi Arabia’s recent spat with the US may well turn out to be a blessing for Amman. King Abdullah II of Jordan recently met with King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia and Crown Prince Nahyan of Abu Dhabi on October 21 in an attempt to further solidify relations between the three nations and build a discussion about the situation in Syria. In attendance were both directors of intelligence for Jordan and Saudi Arabia’s, General Faisal Al Shoubaki and Prince Bandar. This would allude that much of the conversation that took place was about the future of Jordan’s role in the arming of Syrian rebels. Saudi Arabia may find the United States more reluctant to engage in the coordination of arming Syrian rebels after the recent row between the two nations, therefore Saudi Arabia might find itself in need of Jordan and it’s intelligence services. This will give the Hashemite Kingdom more leverage to pursue its own interests. Jordan will therefore be afforded more opportunity to push for its own agenda and not be subjected to one grounded solely in Saudi ambitions.

While domestic apprehensions drawn out by the Syrian conflict have become a recurring security concern for Jordan, the regime has adopted effective strategies to react to these problems. Pragmatism is a term that has come to define the small Jordanian state. Located in a sea of turbulence, Jordan has found a way to cope with its environment and ride out the waves of unrest. However, the bloodier it gets in Syria and the longer the conflict lasts, the greater the risk on Jordan’s stability. For now, though, Jordan seems to have coped much better with the Syrian spillover than many would have expected.

Jaymes Hall is a graduate student at the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University, where he is pursuing a Masters in security policy studies. Mr. Hall previously interned at the Washington DC office of the Institute for Near East and Gulf Military Analysis (INEGMA) and the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

The human face of chemical inspections in Syria

By Egle Murauskaite and Michelle E. Dover – Tasked with the mission of destroying the Syrian government’s chemical weapons capability amidst civil conflict, the United Nations’ Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) faces an immense challenge. This is the first time international inspections and efforts to dismantle a country’s chemical weapons capability are taking place during an active conflict. To effectively protect its inspectors, the OPCW needs a management and support system for what is increasingly looking like a long-term process of engagement in Syria, and possibly a precedent in the making for future inspections.

Presently, international inspectors are working on two parallel tracks. The first effort is the investigation into alleged use, which consists of a fact-finding mission overseen by the United Nations, with assistance from the OPCW and World Health Organization (WHO). The politically sensitive nature of this undertaking has led to a deliberate exclusion of experts from the five permanent state members of the U.N. Security Council from the outset of the mission. This has greatly limited the number of available inspectors, but is likely to be an emerging trend for future fact-finding missions of this kind. The other process is an OPCW-led initiative to verify and dismantle Syria’s chemical weapons program. The team includes some inspectors from the permanent Security Council members, though the organization’s resources were already stretched before it was handed the task of disarming Syria.

While member states have provided financial and in-kind support for both the verification and dismantlement missions, more attention needs to be paid to creating long-term support for the inspectors, considering what the international community is asking them to do. The thin roster of OPCW inspectors (less than 150) sent to the field is working in a horrid environment, which looks nothing like their daily routines in universities or laboratories. Indeed, while the OPCW is starting the process of training experts to become inspectors – by providing them with better understanding on the OPCW legal and political frameworks, teamwork procedures and efficiency in the field, – member states have met this effort with skepticism, preferring to focus their resources on raising the inspectors’ level of technical expertise.

Aside from the complexities of the mission itself, the inspectors are personally taking on a two-fold risk – to their physical and mental wellbeing. First, there is the active risk of injury and the ability to carry out the mission in an active war zone. Inspectors are not trained soldiers – they are usually scientists (chemists, health specialists etc.) conducting research in laboratories or working in academia. Sending these experts into such a dangerous and lawless environment means very real risks to their lives and state of mind. Because the OPCW has never conducted such a complicated mission before, the rules are being established and resources garnered as they go along. However, despite the highest precautions, inspectors in Syria have already been put in harm’s way. Namely, during the first visit of the UN fact finding mission in August 2013, the team was holed up in a Damascus hotel for days during a particularly violent episode that included chemical weapons use in the vicinity. Soon thereafter their convoy came under a sniper attack, but the inspectors completed their task after changing vehicles. In addition, the access negotiated with the Syrian government means that the official minders and security teams provided by the Assad regime cannot accompany the inspectors into rebel-controlled areas, effectively leaving them to fend for themselves in these pockets of contested territory.

The last time that a comparable international inspection was sent to the field was in Iraq in the 1990s. The UNSCOM inspectors there were working in a post-conflict environment, with the worst of the hostilities already over, and yet they were still threatened by Saddam Hussein’s forces firing warning shots over their heads, and holding the inspections team in a parking lot for four days when they refused to give up documents. A relevant mission of destroying chemical weapons stockpiles and precursor facilities was the one carried out in Libya. After joining the Chemical Weapons Convention in 2004, more than half of Libya’s stockpile had been destroyed by 2011, when malfunctioning equipment halted the process and internal instabilities in the aftermath of the Arab uprisings delayed that process until April 2013. Notably, however, during this time, the OPCW had no in-field presence in Libya. In Syria, the problem is considerably worse as efforts to dismantle the country’s chemical weapons capabilities are taking place during an active conflict.

When it comes to the second challenge, the inspectors are witnessing the horrors of war, including interviews and visits of the victims of the chemical weapons attacks, without being able to intervene –in part due to their mandate, general status as outsiders, and the immensity of the conflict. The international community has witnessed a similar personal tragedy of Canada’s Romeo Dallaire and his small UN contingent in the unfolding genocide in Rwanda. With no international structure to support his efforts and limited resources, in the aftermath he spoke out countless times about facing the dilemma of helplessness, alongside increasing personal risks to his team and himself, and yet knowing the situation would only get worse if he and his men withdrew. Dallaire subsequently became a prominent international figure and advocate for human rights, but the conflict left him scarred with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and he has attempted suicide.

The United Nations and OPCW should provide the appropriate support to the inspectors they currently have on the roster, as well as begin to train others to lessen the burden on that group. Both organizations should ensure inspectors receive continued training for working in conflict zones, as well as institutional support once they are in the field. In light of the growing recognition of PTSD, mental health support should be made available for inspectors upon their return, especially if they are asked to deploy to Syria more than once under current expert shortages. Both the United Nations and OPCW should aim to expand their circle of trained experts, with a focus on finding non-P5 experts in the short-term and making connections with new pools of expertise in universities and laboratories in the long-term.

When looking at the small number of inspectors against the overwhelming number of casualties in the war, it is easy to argue that the cost – as Jeremy Shapiro framed it in the Economist, “the mental health of a few mid-level officials in the US government” – is minimal. However, the OPCW experience in Syria is paving the way for future practices in inspections and weapons of mass destruction disarmament missions. The individual costs and personal courage should not be discounted, even in light of such great tragedy as chemical and conventional weapons use in Syria. To attract and maintain the expertise the world needs for these challenging and complex tasks, the inspectors should not be overlooked.

Egle Murauskaite and Michelle E. Dover are Research Associates at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS).

These are all weaknesses in th

Richard! Does Aussie Dave know

Postol's latest publication ab

Mr. Rubin, I am curious if you

Thank you Uzi. You have obviou

Bruce came back to CSTPV's 20t

Bruce came back to CSTPV's 20t

Thanks for publishing in detai

The 'deal' also leaves Israel

I think that Geneva Talks pose