The false promise of a piecemeal approach to a WMD-free Middle East

By Bilal Y. Saab – Almost two decades have passed since the Middle East Resolution – agreed by the 1995 Review and Extension Conference of the Parties to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty – called to rid the region of all weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Yet the Middle East remains a heavily militarised theatre of conflict awash with such capabilities, and is still very far from the goal of disarmament.

There is no single reason why regional states have failed to create a WMD-free zone. A mixture of politics, prestige and security considerations have conspired to delay indefinitely one of the world’s most prized security goals, and international non-proliferation diplomacy’s most urgent priority.

The intention behind the proposed zone was, and still is, to induce security co-operation by addressing head-on the worst fear of regional states: the effects of WMD. The potential elimination of these most lethal weapons, it is assumed, would drastically assuage threat perceptions and thus encourage further self-restraint and co-operation.

It is hard to argue with this idea given its tremendous potential benefits. Yet the reason it has not seen the light of day is that it is an impractical shortcut in dealing with such a complex issue. In a nutshell, it pursues a top-down approach to a problem that can only be solved from the bottom up. It asks too much, too soon, of regional parties who do not yet trust each other and who exist in a dangerous and fluid environment. Disarmament, especially under the present regional circumstances characterised by heightened security concerns and hardened security thinking, is seen by some regional states as pure fantasy. For them, even mere talk of disarmament is a non-starter.

Over the years, frustration with the lack of progress on the WMD-free zone has prompted non-proliferation analysts to think hard about more creative ways to break the diplomatic logjam. Some proposed disaggregating the concept and focusing, in the near term, on the less ambitious goal of a chemical-weapons-free zone, a biological-weapons-free zone or both, if possible. Others counselled, in the spirit of pragmatic gradualism, the adoption of conventional arms-control measures as a way of building confidence between rivals. Such steps include the removal of – or imposition of limitations on – delivery systems, including medium- and long-range missiles.

Given Syria’s current path toward chemical disarmament, if there were ever a time to push aggressively for the elimination of all chemical weapons in the Middle East – and, as such, the fulfilment of one crucial pillar of the WMD-free zone – this is it. In September 2013, Syria was forced to accept the dismantlement of its highly sophisticated chemical-weapons programme after using sarin against its people in Damascus in August – an attack which reportedly killed hundreds, resulting in international outrage and the US-Russian-brokered deal to destroy the weapons.

Because of the civil conflict and the size of the regime’s chemical stockpiles, the full process of decommissioning will be complex, slow and dangerous. It is being conducted in stages, according to an internationally agreed timetable, with the financial, logistical and technical assistance of more than a dozen countries. This process involves, first, weapons being transferred by Russian armoured vehicles from twelve storage sites (mainly in the suburbs of Damascus) to the Russian-secured port of Latakia, tracked by US satellites and Chinese surveillance cameras. At the port, a Danish-Norwegian flotilla is then tasked with transferring the chemicals to international waters, accompanied by naval escorts provided by Russia, China, Denmark, Norway and the UK. The plans then see the stockpile being transported to the port of Gioia Tauro in southern Italy, loaded onto the US vessel Cape Ray, and taken back into international waters to be destroyed by hydrolysis in a titanium tank onboard.

This process is now underway, with the first batch of Syria’s chemicals having been safely loaded onto a Danish cargo ship in the port of Latakia in January. Several previous deadlines established in line with the internationally agreed timetable have, however, been missed. Ambassador Ahmet Uzumcu, director-general of the UN’s Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), the body responsible for the operation, recently said that the process had been delayed due to security concerns, but expressed confidence that the entire stockpile would be destroyed by the new deadline of 30 June. Meanwhile, on 10 February, the OPCW announced that a third shipment of chemicals had been removed from the country. Yet, ultimately, the completion of the job depends on the continued co-operation of the Syrian government and all international actors involved, as well as the ability to secure vehicles travelling overland to Latakia.

The precedent set by this operation is promising. Chemical weapons have inflicted tremendous suffering on the people of the Middle East – in northern Yemen in the 1960s, Iran in the 1980s, Iraq in 1988 and, most recently and tragically, in Syria. It would certainly be a net strategic and moral gain for Middle Eastern countries to outlaw these horrific weapons once and for all. If Egypt and Israel can be incentivised, as well as pressured, to join the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) – which Egypt has not signed, and which Israel has signed but not yet ratified – the Middle East stands a chance of freeing itself of the worst poisons on the planet. (Iran ratified the CWC in 1997.) The same goes for biological weapons. Although there is no evidence of the usage of such weapons in the Middle East, poisonous biological agents are believed to exist in Israeli and Egyptian military arsenals and research labs. Unlike Israel, Egypt is a signatory to the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC), but Cairo has yet to ratify it. Iran, by contrast, signed the BTWC in April 1972 and ratified it the following year.

If only things were so simple. No matter how historic the opportunity provided by Syria, it appears that this will not be enough to fundamentally change the political, psychological and security calculi of regional states regarding WMD disarmament. This is because a pick-and-mix diplomatic approach to a WMD-free zone, regardless of its creativity, will not do the trick. This is not to argue against the formulation of new ways to break the diplomatic stalemate. Perhaps with luck, a truly imaginative political means of solving this intricate challenge might yet emerge. But the point is that, before worrying about style and approach, it is first necessary to understand the basic hurdles: namely the reasons for regional positions and their long-standing persistence. It is not enough to know each country’s preferences and interests; it is necessary to appreciate more fully why they have consistently refused to compromise.

It is essential to assess, for example, why Egypt and Israel have not given up their chemical- and biological-weapons programmes despite the huge security benefits to be gained from doing so. In the case of Egypt, it must be asked what good sarin gas brings the country, other than some imagined diplomatic leverage, and why Cairo has held onto its stockpiles since the First World War. As for Israel, it must be asked why the country has snubbed both the CWC and BTWC in light of the arguably minimal difference this would make, in relative terms, to its security given the country’s possession, unlike any other in the region, of nuclear weapons.

On 25–26 November 2013, Israeli and Arab diplomats met in Switzerland to resume preliminary talks on the WMD-free zone and, specifically, to reach consensus on items and modalities relating to the postponed conference on a WMD-free zone originally due to take place in Finland in 2012. However, as if nothing had changed since the early 1990s, Arab and Israeli envoys could not agree which weapons should be discussed. Israel has always favoured a holistic approach and recommended the inclusion of conventional arms and their delivery systems. Arab states have been adamant in their desire to focus solely on unconventional arsenals.

It is pointless to assign blame for the continued deadlock to one party or to argue which side has a more convincing argument. None has a slam-dunk case, and if all regional parties maintain their positions, the goal of zero WMD will continue to be eluded. The only way to break the cycle is for regional parties to agree to discuss – openly, comprehensively and consistently – their hopes and fears in a collective fashion. This does not have to occur through a major regional security conference, although the benefits of this would be considerable. A series of smaller, more private meetings may do the job. When disagreements are as profound as they currently are, the nature of the venue is, arguably, secondary.

The primary goal is to correctly diagnose this multifaceted problem. All states should come prepared to leave no stone unturned in breaking down traditional barriers and dichotomies – such as conventional-versus-unconventional weapons and notions of ‘peace first, arms control second’ – that are based on faulty logic. Despite having battled in non-proliferation fora for over twenty years, Arabs, Israelis and Iranians still misunderstand each others’ positions and concerns. If this does not change, no progress will ever be made.

Yet it is also clear that the context has shifted dramatically since the arms-control and regional security talks of the 1990s. Most importantly, the issue no longer revolves around a political and legal feud between Egypt and Israel (though it persists to this day), and these countries no longer dominate non-proliferation and regional security talks. Instead, the rise of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and Turkey will force non-proliferation diplomacy to take the views of these states into account as well; gone are the days when Egypt spoke for all Arabs. Then, of course, there is Iran, whose nuclear programme was not a major item of discussion two decades ago, but has now completely reshuffled the deck in terms of non-proliferation diplomacy. These emerging actors add an additional layer of complexity to discussions, which makes the task of understanding their interests and concerns even more important.

Such diplomatic and information-gathering discussions will obviously not suffice to create a Middle East free of WMD. Yet even if this goal is not achieved any time soon, such an exercise would hopefully accomplish one major task: namely the formulation of more accurate assessments of the real causes of the continued lack of progress and the real reasons for regional states’ rigid positions. This is the toughest nut to crack. But if these murky issues can be clarified, further discussions around the optimal approach to a WMD-free zone in the Middle East are likely to be much more fruitful.

This article was first published by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), Newsbrief, March 7, 2014. It is available here.

CW attack in Syria: faulty intelligence or faulty conclusions?

By Uzi Rubin – During the early morning hours of August 21, 2013 a deadly attack of rockets carrying nerve gas was unleashed upon several neighborhoods east and south of Damascus. The world was horrified when the images of piles of corpses, many of them children’s, were flashed on TV screens and through the social networks. A United Nations (UN) mandated inspection team confirmed that a large scale chemical attack has indeed taken place on August 21. With the victims being all residents of districts controlled by the opposition forces, fingers were immediately pointed at the Assad regime as the perpetrator. This was fervently denied by Syrian officials. Russia, while not denying that nerve gas was used, expressed doubts about who used it, hinting that opposition forces may have been the perpetrators of this crime.

The U.S. Administration, basing its judgment on classified information and intelligence assessment, directly accused the Assad regime as the perpetrator. In an August 30 press conference, Secretary of State John Kerry declared that “we know where the rockets came from and at what time… we know the rockets came only from regime controlled areas… We are certain that none of the opposition has the weapons and capacity to affect a strike of this scale, particularly from the heart of the regime territory…” For a short while, it seemed that the U.S. was poised to go to war against the Assad regime, possibly triggering a larger conflict in the Middle East.

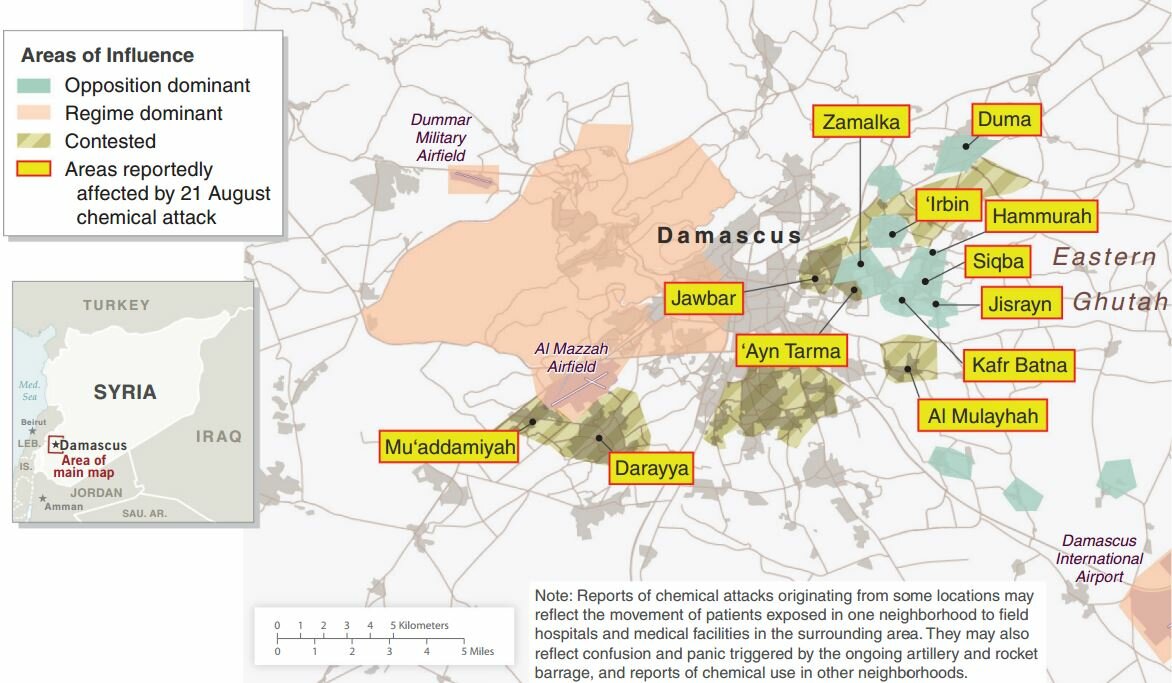

While President Obama pulled back at the last minute from implementing his own implied threat of a forceful retaliation against the Assad regime, it was a close call, in terms of yet another U.S. military intervention in the Middle East, which rattled a number of critics. Several members of Congress contested the Administration’s position. The veteran investigative reporter Seymour Hersh expressed skepticism over the integrity of U.S. intelligence assessment, citing the 1964 Tonkin Gulf precedent of “tailored reports.” On January 14, 2014, Dr. Theodore Postol of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the former UN weapon inspector Richard Lloyd published a study in which they concluded that the 2 km range of the rockets used in the August 21 nerve gas attack in Damascus precluded their launching from “the heart of the regime territory” or from any Syrian government controlled area. To prove their point Postol and Lloyd used a map of government and rebel dominated areas in Damascus published on the White House website (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The White House Map

Furthermore, Postol and Lloyd disputed Secretary Kerry’s statement that the opposition did not have the means to carry out such a strike. According to their study, “the indigenous chemical munitions could be manufactured by anyone who has an access to a machine shop with modest capabilities.” In subsequent interviews, Postol stated that although he had initially believed that the Syrian government was behind the attack, he now “had no idea what really happened.” Lloyd, on the other hand, continues to hold that “the Syrian rebels most definitely have the ability to make these weapons… they might have more ability than the Syrian government.” The authors accused the Obama Administration of taking the nation to the brink of war on the basis of what they termed “erroneous intelligence” and warned that “if the source of the error is not identified …the chances of a future policy disaster will grow with certainty.” The allusion to the 2003 intelligence debacle concerning Saddam’s nonexistent weapons of mass destruction could not be made clearer.

The Postol and Lloyd study and Hersh’s article caused a considerable stir. While the three were careful not to say so explicitly, their publications were interpreted by many as an exoneration of the Assad regime and an implied accusation of the opposition in perpetrating the nerve gas attack – thus supporting both the Assad regime’s and Russia’s contentions. Yet, the study is markedly flawed, because it omits some key facts related to the events while completely ignoring the context in which the attack occurred. When all the known facts weighted, it becomes clear that the Syrian Army was fully capable of hitting the neighborhoods in question with at least two types of chemical rockets, in spite of their limited range; Furthermore, the Syrian Army was fully capable of hitting those neighborhoods from “the heart of the (Assad) regime territory” and from “Syrian controlled areas.”

The Chemical Rocket Attack on Muadamieh

Muadamieh is a town located to the south of Damascus (see Figure 1). At the time of the August 21 chemical attack, the town was under opposition control. Nearby lies the regime controlled Mazzeh airfield, from which the Syrian Army has been operating against both Muadamieh and the nearby town of Darayya. According to the Human Rights Watch report on the Damascus chemical attack, in the early morning hours of August 21, Muadamieh was struck by seven chemical rockets with considerable loss of life.

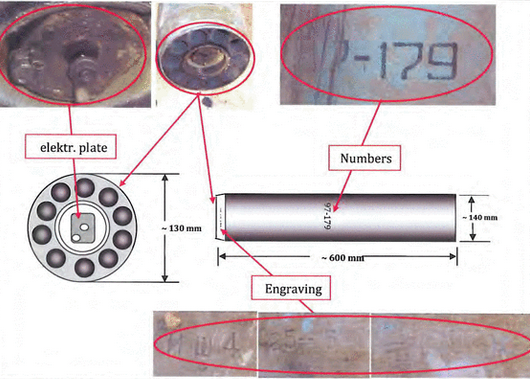

The chemical-armed rocket attack on Muadamieh featured prominently in the UN report (paragraph 28), as well as Human Rights Watch reports. The White House map explicitly marks Muadamieh as one of the affected localities. The attack on Muadamieh could hardly be overlooked or dismissed as a trivial event. Yet, it is completely ignored in the Postol and Lloyd study. The UN team examined the remains of the rockets that struck Muadamieh and determined that they belonged to a140 mm Russian-produced artillery rocket, part of the Soviet era BM 14 system acquired by Syria (see Figure 2). As described by Dr. Igor Sutyagin from RUSI, this type of rocket is still operational within the Russian Navy. One of its variants can carry 2.2 kg of chemical warfare agents. The rocket has a minimum range of 3.8 km and a maximum range of 9.6 km. Based on all available information, including the White House map, the Syrian Government-controlled area at that time abutted Muadamieh all the way to the Presidential Palace and beyond. Therefore, there is no technical reason why the Muadamieh rockets could not have been launched from anywhere between the Syrian Government-controlled Mazzeh airfield and the “Heart of the (Assad) regime territory” – and in all probability, so they were.

Figure 2: 140 mm Rockets Used for CW attack on Muadamieh

(based on the UN Inspectors Report)[1]

From the openly available information it is clear that as far as the Muadamieh attack is concerned, Secretary Kerry’s statement cannot be refuted on account of the rockets’ range.

The Fighting around Damascus and the Chemical Rockets Attacks on Zamalka and EinTarma

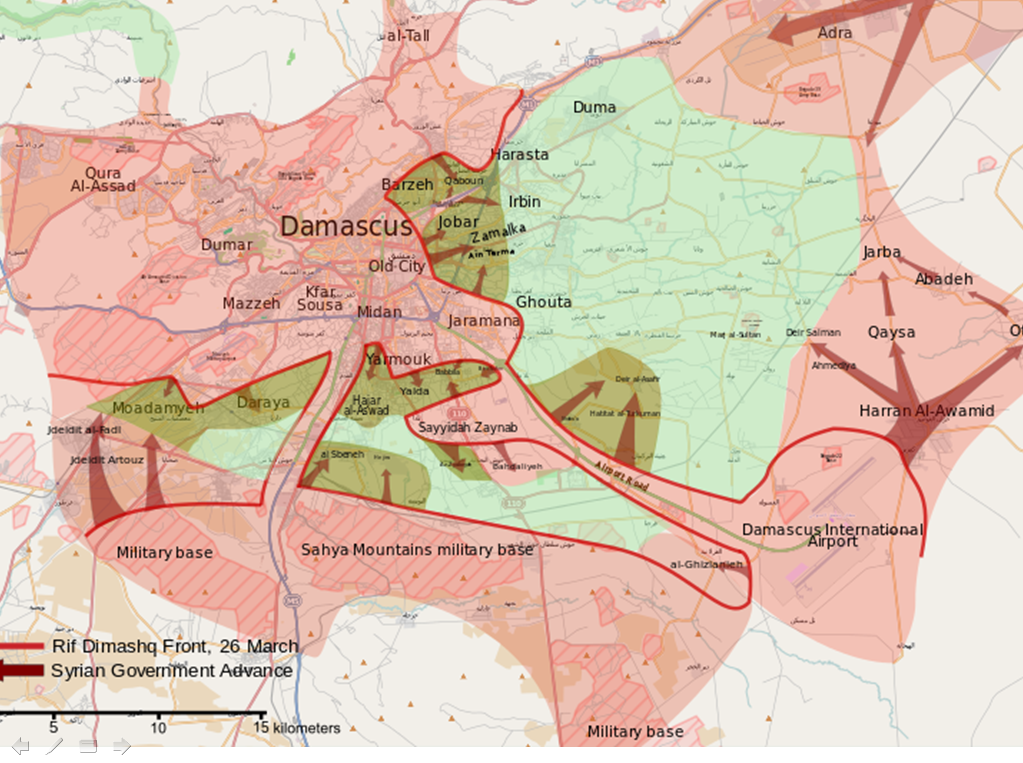

The battles for the neighborhoods around Damascus metropolitan area have been perhaps the fiercest in the still raging Syrian Civil War, since the opposition’s control of many of the suburbs threatened the regime’s very existence. In March 2013, the regime launched the still ongoing Operation Rif Damashq (see Figure 3), aimed to regain control of the entire Damascus province, including the immediate suburbs of Jobar, Zamalka, and other neighborhoods located just few miles away from downtown Damascus.

Figure 3: Operation Rif Damashq (March – August 2013) [2]

The operation consisted of several consecutive offensives. One of those offensives, dubbed “Operation Qaboun,” was apparently launched in June 2013. The operation’s objective was to drive a wedge between the suburbs of Jobar and Qaboun to the west, and the rebel strongholds of Zamalka, EinTarma and Irbin to the east. For this purpose the Syrian Army fought its way into the Jobar Industrial Zone and used it as a staging area to drive its offensive north and south (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Map of Operation Qaboun [3]

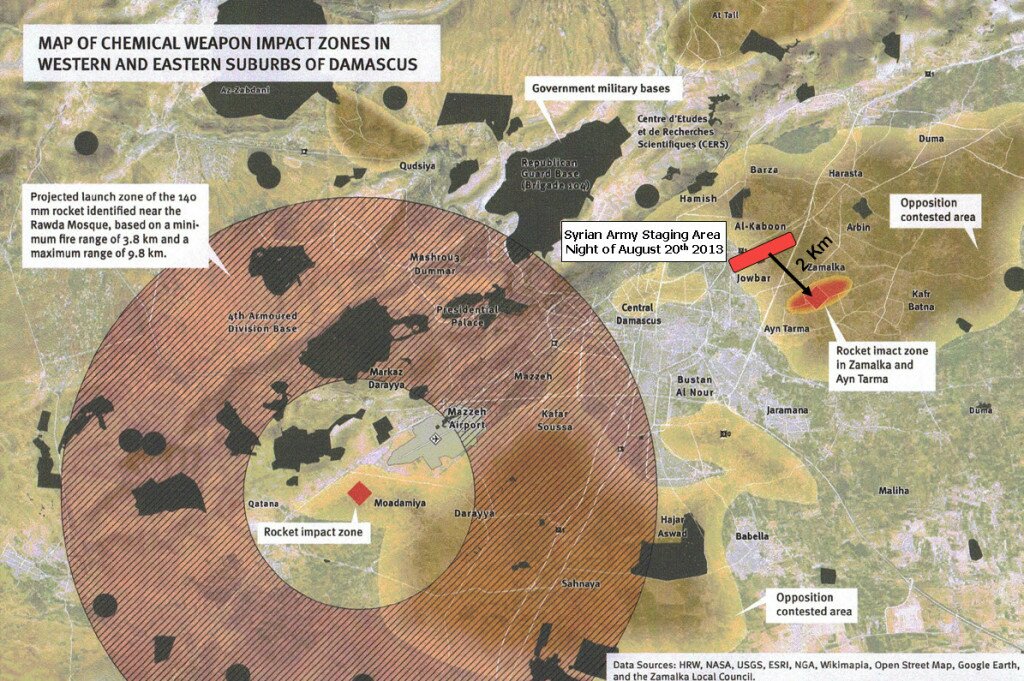

In the eve of the chemical rocket attack of August 21 the Syrian Army was deployed in, and controlling part (if not all) of, the Jobar Industrial Zone, literally a stone’s throw away from the center of the Zamalka and EinTarma districts. Although no official data is available on the precise location of the impact point, the Human Rights Watch report shows 12 impact points concentrated in a 2,100 by 600 meter footprint with its major axis inclined in a north east direction (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Aug. 21 CW rocket impact footprint in EinTarma and Zamalka [4]

The open sources indicate that no other suburb east of Zamalka suffered chemical attacks that night, but that some of the victims from Zamalka and EinTarma were treated in the hospitals of neighboring communities to the east and north. The UN inspection team identified the weapons used in this attack and dubbed them“330 mm” rockets (see Figure 6). In their January 2014 study, Postol and Lloyd calculated the maximum range of those “330 mm” rockets as 2 Kilometers, arguing Zamalka and Ein Tamra were therefore out of range from Regime dominated areas.

Figure 6: “330mm Rockets” used in CW attack on EinTarma and Zamalka

(based on the UN Inspectors Report)

However, as can be seen on the larger scale map provided by the Human Watch Report (see Figure 7), the distance from the Jobar Industrial Zone to the center of the impact footprint is about 2 km. This means that Syrian Army deployed there was capable of hitting Zamalka and EinTarma from regime-controlled areas in spite of the short range of the weapons used in this case. Therefore, allegation of U.S. “erroneous intelligence” on account of the short ranges of the rockets employed is groundless.

Figure 7: August 21st 2013 CW rocket impact zones

(Highlighting of Jobar Industrial Zone and its distance from Zamalka Impacts footprint

added by the author)

Whose Rockets?

One of the key arguments in the Postol and Lloyd study is that the “330 mm rockets” identified by the UN inspection team as the delivery platforms in Zamalka were simple enough to be produced by anyone with access to a machine shop. However, a closer examination indicates that the rockets used were not some jury rigged improvisations, but carefully thought out and designed weapon systems corresponding with Syrian Army’s operational needs. Their development and manufacturing required some proficiency in rocket engineering and their firing – fairly complex mobile launchers. Furthermore, the publicly available records clearly show similar weapons being used repeatedly during the civil war by the Assad regime.

When seen in the context of the Syrian Civil War and the regime’s methods and needs to overcome the opposition, and when compared to similar weapons used by the regime in other instances, it is more likely than not that it was the Syrian Army that launched the Zamalka and EinTarma chemical rockets.

With the onset of the Syrian Civil War and the fighting for control of urban areas, the Assad regime sought to overcome resistance by indiscriminate bombardment of opposition-controlled neighborhoods by air dropped bombs. When the fighting intensified and when opposition’s man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS) started to pose a threat to the Syrian Air Force, the regime reverted to the use of heavy rockets and ballistic missiles – including SCUDs – in its attacks. According to a ranking officer in Israel, by May 2013 the regime may have consumed almost one half of its ballistic missile arsenal in the attacks against opposition-held cities and neighborhoods.

Towards the end of 2013, reports of ballistic missile attacks started tapering off. It stands to reason that the Syrian regime, considering missiles as the core of its strategic deterrent against Israel, was reluctant to squander them in the Civil War. Cheaper, mass producible, non-strategic but nevertheless heavy weapons were needed for the job. Parallel to the onset of ballistic missile attacks, new types of “popsicle” shaped short range rockets started to make an appearance in the battlefields. Those rockets, dubbed “Volcano,” came in three sizes – light (see Figure 8), (see Figure 9) and heavy (see Figure 10). All three rockets seem to consist of standard artillery rocket motors mated with oversized warheads. The light version is based on the standard 107 mm rocket and is spin stabilized, while the medium and heavy versions seem to be based on the 122 mm Grad rocket motor, and (possibly) the Russian designed but Syrian manufactured 220 mm artillery rocket, respectively. The latter two possess enhanced stabilizing tail assemblies similar in design to the tails of the “330 mm” rocket.

Figures 8-10: The Three sizes of “Volcano” rockets

All three types seem to be designed for simplicity and mass production, providing the Syrian Army with heavy firepower at close ranges where accuracy was not too important – that is, for urban warfare. Significantly, they have all been observed in operation by the Syrian regime forces.

The medium and heavy “Volcanos” are launched from fairly complex truck mounted assemblies with mechanical traversing and hydraulic elevation mechanisms. The trucks are equipped with leveling stabilizers. Their design bears the fingerprints of professional, experienced missile engineering teams, rather than jury rigged piecemeal improvisations made in local machine shops. The similarity between the double-barreled medium “Volcano” launcher to the Iranian “Falaque” mine clearing rocket launcher is striking.

It seems that all three types of “Volcano” rockets are normally equipped with explosive warheads (the heavy “Volcano’s” warhead might weigh one ton, comparable to a SCUD B warhead). The fact that the Assad regime freely advertises their existence indicates that the regime views them as legitimate conventional weapons.

The “330 mm” CW rockets discovered in Zamalka and Ein Tarma are virtually indistinguishable from the medium “Volcano” rockets, save for the adaptation of the warhead sections for filling with liquid payloads (Sarin chemical agent). Their motors consist of the rear half of standard Grad 122mm rockets. However, instead of the original free standing double-base (“smokeless powder”) propellant, the “Volcano” motor is cast from more powerful, aluminized composite propellant, as can be clearly seen from its white exhaust flame and thick smoke trail (see a comparison with the reddish flame and thin smoke of a regular Grad rocket in Figure 11). Furthermore, at least one video clip of a medium “Volcano” flight indicates that the new propellant is faster burning than the original one, presumably to compensate for the reduced burning surface of a “half length” motor. All these are indicative of proficient engineering and production means of its makers.

Figure 11: Comparison between “volcano” and “Grad” rockets flame

While all this does not preclude the possibility that the opposition has managed to procure or build up a fairly professional rocket R&D and production infrastructure in the remarkably short time of three years, its likelihood seems remote. It is more likely that the medium “Volcano” aka the “330 mm” CW rocket with its customized motor and elaborate launcher is the product of the selfsame experienced Syrian missile industry that have evolved and produced the heavy 300 km range GPS guided “Tishrin” smart rocket – the likes of which are clearly beyond the capability of the opposition’s rudimentary machine shops.

Conclusions

There is enough evidence in the public domain to conclude, with a fair degree of certainty, that the Syrian Army could and did launch the chemical rocket attacks on Muadamieh, Zamalka and EinTarma on August 21, 2013. In the case of Muadamieh, the Assad regime possessed 140mm rockets with enough range to hit the town from the “Heart of the Regime’s territory.” In the case of Zamalka and EinTarma, the Syrian Army was deployed close enough to hit those neighborhoods with the shorter range “Volcano”/ “330 mm” rockets from regime controlled territory. The “330 mm” rockets discovered in Zamalka and Ein Tarma were not improvised, jury rigged devices that could be casually made in any workshop; rather, they were part of a well designed range of weapon systems contrived to fulfill Syrian Army’s operational needs. Therefore, Secretary Kerry’s statements did not reflect “erroneous intelligence,” but rather a sensible conclusion that, in fact, could be largely derived from information in the public domain. Whatever assessment U.S. intelligence provided the Administration with, there is no reason to believe that it was “erroneous.”

Why did Postol and Lloyd arrive at such faulty conclusions? First, because they ignored the Muadamieh chemical attack and its implications; second, because they wrongly assumed that the Syrian Army could not operate beyond the regime dominated areas marked out on the White House map; and third, because they ignored the context of the attacks. When the Muadamieh attack, the presence of the Syrian Army outside of the regime dominated area, and the fact that the attacks were carried out as part of a Syria Army offensive to regain the areas that came under its attack are all factored in, everything falls in place. The alternative – that the opposition launched a chemical attack on its own forces amidst a raging Syrian Army offensive against it – stretches credulity to its limits.

This is not to say that the U.S. should have gone to war to punish the Assad regime. If anything, the wisdom of drawing a “red line” over the use of chemical weapons – or for anything else in this war – could be questioned. Yet, one troubling riddle remains unanswered. In 2005, when Lebanon’s Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri was assassinated, U.S. President Bush and France’s President Chirac pushed for a UN Security Council resolution establishing a court of inquiry to find and indict the assassins. Yet, in 2013, the horrific chemical rocket attacks in Damascus, defined by the UN Secretary General as “grave violation of international law” elicited no similar call for UN mandated board of inquiry to determine responsibility and deliver justice. Neither President Obama, nor his opponents in Congress, or any Western government demanded that the persons responsible for this crime against humanity be identified and punished. This, and not the capability of the Syrian Army to launch the August 21, 2013 chemical weapons attacks, will forever remain the great enigma of this entire tragic affair.

Final note: the Syrian Civil War is truly an Internet Age conflict, where the antagonists strive to dominate the cognitive battlefield by flooding the Web with visual information, and with armchair reporters supplementing, if not replacing, traditional war journalism. Public domain information is overwhelmingly available and is freely assessed by professional and amateur analysts. The most noticeable home watcher of the Syrian conflict is Mr. Elliot Higgins of Leicester, UK, publishing his blog under the alias of “Brown Moses.” Most of the information on which this paper is based regarding weapons and operations in the Syrian Civil War comes from his blog (unless otherwise indicated). To Mr. Higgins I owe a debt of gratitude for his generous public sharing of the fruit of his hard work.

Uzi Rubin was the first Director of Israel Missile Defense Organization. Between 1991 and 1999, he oversaw the development of Israel’s Arrow anti-missile defense system. He was awarded the Israel Defense Prize in 1996 and 2003.

These are all weaknesses in th

Richard! Does Aussie Dave know

Postol's latest publication ab

Mr. Rubin, I am curious if you

Thank you Uzi. You have obviou

Bruce came back to CSTPV's 20t

Bruce came back to CSTPV's 20t

Thanks for publishing in detai

The 'deal' also leaves Israel

I think that Geneva Talks pose